The Chinese have traditionally viewed calligraphy, the art of writing pictographs, as the supreme art form. In China, all the fine arts sanctioned by traditional scholar-artists – painting, calligraphy, and seal-carving – maintain an intimate relationship with the art of the word. Most of the nine Chinese artists whose paintings, sculptures, prints, graffiti, and computer works are presented in this exhibition step outside the calligraphic tradition to both celebrate and critique the conventions associated with the written word.

The Chinese writing system has remained largely stable for more than two thousand years, consequently the system of characters, syntax, and grammar of calligraphic art carries many aesthetic and cultural connotations in traditional Chinese society. The reinterpretation of the calligraphic word by contemporary artists demonstrates a recognition of this cultural power and its significance in shaping the visual sensibility if the Chinese mind. These contemporary permutations also reflect a shaping of the relationship between language and art, many of which are stimulated by interaction with Western culture.

The selection of works for this exhibition bypasses the conventional Chinese aesthetic judgment of calligraphy, which emphasizes the cultivation of an artist’s moral character, and views the written word as an expression of that character. Some of the works interpret the art of the calligraphic word in terms of its visual impact; others elucidate the parameters of the written word as pictorial art; while still others reflect on Chinese calligraphic tradition from the perspective of foreign cultures, where the meaning of Chinese writing becomes invalid or relative.

Many artists in this exhibition introduce an element of absurdity and formal anti-narrative within calligraphic art by undoing the pretense of “meaning” through misprinted, wrongly written, over written, Anglicized, or invented word forms. Others question the “moral character” of the calligraphic stroke by adopting mechanistic postures and procedures, while others explore the written word with regard to its function as a pronouncement of power or as edict.

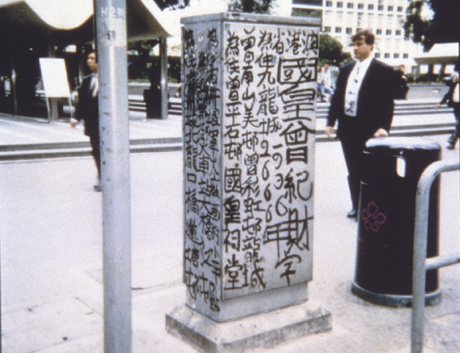

Among the artists included in the exhibition are Gu Wenda (Shanghai/New York), Xu Bing (Beijing), Fung Ming-chip (Hong Kong/New York), Wu Shanzuan (Shanghai/Iceland), Qiu Zi-jie (Xiamen) and Mao Zedong who carried the tradition of imperial calligraphy to its ultimate limit during his rule. The exhibition also includes the work of two “outsider” artists whose work demonstrates the power of Chinese words to shape the way illiterate (or barely literate) people visualize the world: Hung Tung (Taiwan) and King of Kowloon (Kowloon/Hong Kong). In addition, the exhibition presents an interactive computer work by Wang Yong-ming, the inventor of the most successful computer in-put system of Chinese characters. Lauded as revolutionary, this system echoes an analysis of the visual structure of Chinese word forms contrived by calligraphers of past dynasties.