Can artists be successful in creating systems for contemporary art production and interpretation?

Late last year, one of Vietnams pioneering artists, Vu Dan Tan, passed away at the age of 63. He was a wiry, grey bearded man who loved the feel of paper and performance. Known for his vigorous body acts with paint, Vu was a man who had traced the journey from Vietnam to Cuba by train and boat in 1973, stopping in Beijing and Russia his feet never touching capitalist ground. From 1987-1990, Vu lived in Moscow, where he was exposed to the artistic freedoms enabled under Russias Perestroika (political and economic reforms). His memory was vivid of how much these journeys had compelled him to examine the notion of independent thinking in Communist Vietnam thus he started Salon Natasha in 1990, Vietnams first independent art space, where he encouraged artists in Hanoi to gather, chat and exhibit their work. It is this idea of arrival and departure; of fleeing and returning, of choosing and creating that I shall focus on in this DISPATCH. It is a sensitive topic in Vietnam, tempered by the remnants of colonial structures of social and educational life; a history of perceived betrayal towards refugees who have returned and a growing young elite who have successfully sought a foreign education.

Throughout April and May, I will facilitate and present a series of interviews with pioneering Vietnamese artists who have made their own journeys in these aforementioned contexts, returning to begin their own organizational initiatives. I hope their sharing of experience and artistic motivation will provide crucial insight as to how artists are embracing the potential of Vietnamese art, to struggle in the re-shaping of the fragile and complex cultural landscape that is Vietnam today.

Artist Vu Dan Tan and curator Zoe Butt in Vu Dan Tan’s studio, Hanoi, Vietnam. July 2009

Artist Vu Dan Tan and his wife and curator Natasha Kraevskaia, outside ‘Salon Natasha’ – Vietnam’s first artist-run gallery in Hanoi, Vietnam

A few facts

Since 1986, when Vietnams economic reforms began (locally known as Doi Moi which is loosely recognized as a socialist-oriented market economy) , the craze of economic progress has continued to buzz in the steady drone of motorbikes as they carry young professionals towards the shining claim of the US greenback. The countrys highways are increasingly following the metropolis mud map of layered loop roads and, like many countries in South East Asia, Vietnam remains one of the worlds top tourist destinations with a steady injection of foreign multinational brands claiming prime real estate on coastal and city fronts. Never before has Vietnam felt so vibrant in its eagerness to test its new and expanding strength (in 2010 Vietnam ranks as holding the highest ranking GDP in South East Asia at an expected 5.9%).

At a cursory glance, Vietnam appears to be a country of immense opportunity, and indeed in many ways its mercantile potential is a driving force for both local and foreign investors. However with consideration to art and education in Vietnam, its meaning and relevance in defining this countrys cultural identity, is still a heavily guarded topic. To demonstrate this reality, a few general, yet revealing facts concerning culture, education, and arts infrastructure in Vietnam are listed here:

The Cultural Ministry of the Vietnamese Communist Government must approve all cultural public events and publication of associated textual material (which includes visual art related activities, such as exhibitions).

The art education curriculum in Vietnam is modeled on the French École des Beaux-Arts system (established in Hanoi in 1924 during the French occupation of Indochine), which focuses on the technical application of the plastic arts (sculpture, drawing, painting, lacquer, silk screen and printmaking).

University art libraries have little visual, textual or theoretical material on international contemporary art production post 1975.

The word for installation is Ngh? thu?t s?p ??t in Vietnamese, which literally translates as art install’. It was coined in the early 1990s (the term installation began circulating internationally from 1969).

Vietnam established an Association for the Fine Arts in 1957, following the precedent of numerous communist countries. Membership within this association was once considered a national accolade, however in the last 10 years, with an increasing number of emerging artists turning towards the foreign art market, its reputation is waning. Despite this trend, this Association continues to function as the key government institution controlling the production of art in the country.

The government is eager to assess the monetary value of art production that is readily exported, looking towards China as a leading example of the marriage between art and tourism. However their understanding of how value is attributed to a work of art follows the national agenda of the Department of Culture, Sports and Tourism which states The cultural sectors targets this year are to raise the cultural and spiritual life of the people, promote traditional and cultural values and teach the tradition of patriotism to build a better country . As a result, the government supports the export of art forms that follow traditional media. Thus Vietnamese artists regularly exhibiting abroad have very little, if any, exposure within Vietnam.

There is no such thing as not for profit as a legal entity in Vietnam.

The only financial support available to artists seeking an independent voice (ie. seeking a critical perspective within their artwork that is not governed by official dictum) is through three foreign NGOs (Alliance Francaise, Goethe Institute, Danish Cultural Consulate).

In May 2009, Time published an article surveying recent evidence that a large majority of paintings and sculptures in the collection of the Fine Arts Museum in Hanoi were forgeries.

There is no public cultural institution in Vietnam that collects contemporary Vietnamese art.

Interview with Rich Streitmatter-Tran, Dia/Projects

Published June 16, 2010

Zoe Butt: As a Vietnamese artist with a refugee history, who was trained in interrelated media in the US, who has worked very closely, indeed collaboratively, with other Vietnamese artists based in Saigon, what were the largest obstacles you faced when you returned to live here in 2003?

Richard Streitmatter-Tran: Actually, to clarify, I don’t fall into the refugee category, as I was an adoptee and my coming to the US was by plane as an infant. So, I never really identified with the refugee experience directly. In 2003, I finished my studies at the Massachusetts College of Art where I was then interested in performance work. I had the privilege of meeting two Vietnamese creatives in Boston, Ngo Thai Uyen and Nguyen Long, who were studying for a semester at the college. That set up for a discussion about the future and later that year, I found myself developing a video art pilot course at the Ho Chi MInh Fine Arts University and forming a performance group. The reason I mention this background is that these early relationships would set a tone for practically everything I’ve done in Vietnam since. In the years say between 2003-2006, art seemed boundless and we had a lot of energy. It was a very exciting time for our art group of five people. But it was short lived. During those years, we had a few confrontations with the government, but ones we were able to work through and move on. I think the hardest challenge was to keep momentum. Unfortunately, our group dissolved a year later on good terms, and I was forced out of the University at the same time. So I had to reassess what I was going to do. I felt a connection with young artists then that I do not have now. I think connecting to young artists and relating to them now, particularly if I didnt have an institutional umbrella, would be difficult. So while I appear to be deeply ingrained into the contemporary art scene here, I feel my depth is rather limited. I have been in the processes of realizing what I can contribute to and what is beyond my scope, aptitude, ability or interest. Beyond simply producing work, I’ve also been asked to wear different hats from arts advisement, awards nomination panels, writing texts for catalogs and other publications and contributing to various research projects. While I appreciate these opportunities, if not properly aligned with my current concerns, they detract from time in the studio producing my work. It’s not a line drawn in the sand, but it’s something that I’ve had to always negotiate – the role as an artist and my other responsibilities.

Interview with Nguyen Manh Hung, artist and Nha San Studio manager

Published June 4, 2010

Pham Ngoc Duong, Cube Statue, at group show “10+”, December 2008

Zoe Butt: My various visits to Hanoi have always included an evening at Nhasan Studio. Tran Luong and Nguyen Manh Duc always present with a steady rotation of other ‘family’ members dropping by to share tea or food. This ‘family’ of artists is quite unique in Vietnam, sitting in a traditional stilt house surrounded by so many antique Buddha figures. You have been an artist nourished by this community and now a part of the second generation to manage this space – from your perspective, are their particular differences between the older and younger generations expectations of this space today?

Nguyen Manh Hung: I have known Nhasan Studio and observed Nhasan activities since 2000. I have seen the development of the Vietnamese art scene through exhibitions of artists and the relationship between them at Nhasan Studio. A lot of generations of artists have participated in and brought many experimental ideas and concepts here. The difference between the younger and the older generation in Vietnam is the freshness and confidence of youth. The older generation (those born in the 1960s) often used the material that concerns their past – the historical past of the country, of living a social ideology. Up until the late 1990s, information, education and networks with the international community outside Vietnam were very rare. Artists had to research and experiment by themselves. Sometimes they misunderstood the languages of media that they were dealing with: installation art and design or decorative objects, performance and theater or improvisational dance. Anyway their experimentation led the path for the new generation to search for experience and develop more professionally. Examining history is not the only reason or material referred to create art by the younger generation. A lot of young artists focus on their own life and physical body. The young artists bring art to the public and give better influences to their environment. So the idea of making art is still also coming from the social sphere, just more diversified.

Interview with The Propeller Group: Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Phu Nam Thuc Ha, and Matt Lucero

Published May 13, 2010

Nh?p ??p Gi?c M? – Hoàng Thùy Linh from The Propeller Group on Vimeo.

Flooded McDonald’s from Superflex on Vimeo.

Zoe Butt: The Propeller Group (TPG) was founded by Tuan Andrew Nguyen and Phu Nam Thuc Ha in late 2006. It was formed as collaboration between creative individuals who wanted to work together to create more ambitious projects in the art context as well as support each other in a commercial context. You were two independent artists interested in the youth culture of Vietnam and fascinated with the way Vietnamese society used television as the key artery for learning what was happening in the world. In 2008, you started to work in collaboration with Danish artist collective Superflex in the making of The Burning Car Movie, which has subsequently toured internationally. In 2009, LA artist and close friend, Matt Lucero joined forces and moved to Ho Chi Minh City (Matt and Tuan had been collaborating since their Cal-Arts days in 2002). The Propeller Group have gone on to produce a diverse range of work from popular music videos with top Vietnamese pop singers, to producing and writing television content for local audiences, to co-producing with Superflex, a collaborative video/television piece for gallery and television audiences with Porcelain, which is your most recent work and will air in the USA and Vietnam in the coming months, while also enjoying a museum focus in the Netherlands. This is an elaborate process of communication and production. If there was one sentence or a word that you would want to use to describe the way that you guys work what would it be?

Phu Nam Thuc Ha: Collaborative.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: I’ve been thinking about our process a lot lately.

Matt Lucero: Multivalent.

Interview with Kim Ngoc, artist, composer, and founder, Hanoi New Music

Published April 29, 2010

Video clip by Brian Ring.

Zoe Butt: I have been fascinated by the ways in which young musicians in Vietnam seem enamored by the pop genre of music. It seems like such a ubiquitous style and trend here. Im also quite struck by the few local or international music events held across the country that showcase different styles of music, of course there are the rare evenings of little known international guests, sponsored by the Goethe Institute or Alliance Francaise, but on the whole, Vietnam seems to lack a continual showing of contemporary music and performance. I am interested to know more about your personal story of travel and inspiration and what drew you to start thinking of conceiving the New Music Festival. Can you tell me a little bit about yourself, your background and how your journeying affected your artistic practice?

Kim Ngoc: As a child of 6 years old, I began studying piano at the Hanoi National Conservatory of Music (now called the Hanoi National Academy of Music). I finished my secondary degree to then continue with a degree in composition at the same institution. After I graduated, I traveled to Cologne in Germany to study with a DAAD Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst (German Academic Exchange Service) (http://www.daad.de) scholarship. In Cologne I continued my study of composition with Johannes Fritsch and improvisation with Paolo Alvares.

Interview with Dinh Q Le, artist and co-founder of San Art, Ho Chi Minh City

Published April 16, 2010

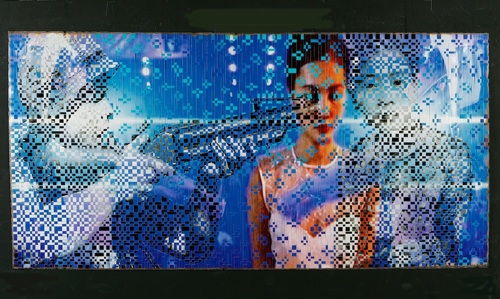

Dinh Q Le, from From Vietnam to Hollywood

Zoe Butt: In 1993, you returned to Vietnam for the first time since your family in the border town of Ha Tien had fled the horror of atrocity during the Vietnam and Cambodia War in 1978. Your study in Southern California, as a refugee and an immigrant at this time could be said to be heavily influential in guiding your principles and opinions as a practicing artist to this day. As this series of interviews for DISPATCH seeks to give insight as to how the processes of movement (as an experience of tourism, necessity or education in living/traveling to different locale), how would you say your movement between Vietnam and the USA has shaped the kind of work that you do today, particularly in relation to your establishment of the Vietnam Foundation for the Arts and the independent art space and reading room, San Art in Ho Chi Minh City?

Dinh Q Le: My movement between Vietnam and the States is frequent and desired. Much of my immediate family resides in Southern California. As a child growing up in Simi Valley, California with the distant memories of a country whose culture and imagery was being fed back to me via mainstream television and film, it was at times difficult to pinpoint which memories were mine or popularly inherited (this was a topic I pored over in From Vietnam to Hollywood a photo-tapestry series and The Imaginary Country a 4-channel video installation). This was also one of the reasons I chose to return to Vietnam to determine for myself my own memories and contexts of who I was as a Vietnamese.

DOCLAB interview with filmmaker, artist and founder, Nguy?n Trinh Thi

Published April 1, 2010

Zoe Butt: For this issue of DISPATCH I am looking at ideas of movement, how artists move from birthplace, to place of work, to place of study, to place of safety, to place of family, to end up building places of critical artistic initiative. I am intrigued by three kinds of stories. Firstly, narratives of arrival and departure (examining the nature of tourism as a means of seeing); secondly, of fleeing and betrayal (here in thinking of the boat refugee community who are now Viet Kieu) and finally, this idea of choosing and creating (here in reference to those who choose to study abroad). In particular I am looking at how this kind of movement is creating a new kind of cultural landscape in the post war generation in Vietnam signaling a new trend of openness whereby old prejudices are ebbing and ideas of what constitutes international within Vietnam being redefined. I wanted to do this interview with you as you are someone who chose to pursue a post graduate degree abroad and have subsequently returned to begin a film initiative in Hanoi that is quite different to what you set out to study. Can you tell me a little more about your family, their opinions of education, and what made you desire to study journalism abroad?

Nguy?n Trinh Thi: Up until the early 90s’ there was virtually only one choice for education in Vietnam. That is the state-managed public system with one single kind of socialist propaganda mindset. I think this was similar to China until the early 1980s. So the only study-abroad opportunity was for the best students to study in Eastern European countries like the Soviet Union, Poland or East Germany for example. Studying abroad even in Eastern Europe was a dream for every student in Vietnam. After I graduated from Hanoi Foreign Language College with Russian and English majors, I started to work as a reporter for an Australian-run English language business weekly called the Vietnam Investment Review. My parents didn’t play much role in my choice of career or education. My mom worked for the Central Documentary Film Studio all her life. But I never thought I would ever work for them. In the mid 1990s, the Ford Foundation started to give scholarships to Vietnamese to study in the US, but only through the government channel and only to a few sectors in the government. However, its first director in Vietnam, Mark Sidel (also a university professor) wanted to help young Vietnamese journalists to study in the US, so he helped me to apply to the University of Iowa. In the end of 1997, I finally got all the funding secured for my degree with a research position, including accommodation and boarding sponsorship from a Viet Kieu family who ran a restaurant near the university. Prior to 1997, Vietnamese government policy did not allow its citizens to study journalism abroad, but fortunately Vietnam signed an agreement with the United States on the freedom of migration, and Vietnamese citizens didnt have to apply for an exit visa anymore. In the early 1990s, options for work had opened up a lot in Vietnam. You can now work for the private sector, for foreign companies or organizations. Young people, who have the chance, prefer not to work for the state.

Visual Context

A typical tourist haven for ‘art made on demand’ in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Hanoi Fine Arts Association

Students of the Painting Department at the Ho Chi Minh Fine Arts University, Vietnam. July 2009

The Curator’s Perspective: Zoe Butt

PPOW Gallery

511 West 25th Street, 3rd Floor

New York, NY 10001

6:30-8:30pm

July 14, 2010

On Wednesday, July 14, Zoe Butt, a curator who has worked with some of the most relevant institutions pushing the discourse of contemporary Asian art, will talk about particular experiences, testing new frontiers collaborating with artists to forge new practices of both curation and creation in the volatile world of China, Vietnam and across the global south. Zoe will be specifically discussing Xu Zhens The Starving of Sudan project; Yang Shaobins X-Blindspot project and Dinh Q Les Farmers and the Helicopters project, placing these works within the context of Vietnam, and her work at San Art in Ho Chi Minh City.

This event will be preceded by a small wine reception at 6:30 pm. The Curators Perspective is free of charge and open to the public, though seating is limited. To RSVP please contact Chelsea Haines at chelsea@curatorsintl.org or 212-254-8200 x26.

Learn more about this event here.

Continuing the Conversation at DISPATCH

The following artists will be featured in DISPATCH in April and May via interview with the author. The following are shared links to relevant works of art, and organizational information.

![]() with filmmaker, artist and founder, Nguy?n Trinh Thi

with filmmaker, artist and founder, Nguy?n Trinh Thi

DOCLAB is a center/lab for documentary filmmaking and video art based at the Goethe Institute in Hanoi. Its activities include basic film and video training, workshops, screenings and discussion, an editing lab and video library accessible to the public.

Read Nguy?n Trinh Thi’s interview here.

with artist and co-founder, Dinh Q Le

with artist and co-founder, Dinh Q Le

Sàn Art is an independent, artist-run exhibition space and reading room located in Ho Chi Minh City. Dedicated to the exchange and cultivation of contemporary art in Vietnam. We aim to support the countrys thriving artist community by creating opportunities that provide exhibition space, residency programs for young artists, lecture series and an exchange program that invites international artists/curators to organize or collaborate on exhibitions.

Read Dinh Q Le’s interview here.

with artists and co-founders, Tuan Andrew Nguyen and Phu Nam Thuc Ha

with artists and co-founders, Tuan Andrew Nguyen and Phu Nam Thuc Ha

The Propeller Group is a collective composed of visual artists from Saigon and LA namely Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Phu Nam Thuc Ha, and Matt Lucero. Drawn to television, film, video and the Internet, The Propeller Group are masters of the language of the moving image, keen to reach a larger audience that takes the presentation of art beyond the world of gallery spaces and museums. Established as a creative content development and production company, The Propeller Group work with local and international film, television, music and artistic producers in the realization of collaborative statements that re-define the social, cultural and political understanding of contemporary culture. Their work has not only been aired on mainstream television and international film festivals, but also in major museums and galleries abroad.

Porcelain from The Propeller Group on Vimeo.

Visit The Propeller Group’s website.

Read The Propeller Group’s interview here.

with artist, composer and founder, Kim Ngoc

with artist, composer and founder, Kim Ngoc

The Hanoi New Music Meeting 2009 was a pioneering event that brought together the best experimental contemporary composers in Vietnam and renowned international artists. The event opens a window on Vietnamese contemporary music not only for audiences, but also for musicians working in different contemporary music scenes around the world. An important aim of the festival was to create a global network that will enable Vietnamese musicians to build up long-term relationships with international festivals and with professional composers and orchestras from around the world.

Visit Hanoi New Music’s website.

Read Kim Ngoc’s interview here.

Nha San Studio with artist and manager, Nguyen Manh Hung

Nha San Studio with artist and manager, Nguyen Manh Hung

Nhasan studio is a traditional wooden house on stilts that was built in 1992 by Nguyen Manh Duc. In 1998 Tran Luong and Nguyen Manh Duc turned Nhasan studio into an experimental art space. Nhasan studio was among the first alternative and non profit spaces for contemporary art not only in Hanoi, but also the whole country. It opens for local and international artists to present new kinds of media such as video, performance, sound, music, installation and much more.

Visit Nha San Studio’s website.

Read Nguyen Manh Hung’s interview here.

Dia/Projects is a new space for contemporary art in Ho Chi Minh City established in March 2010. It functions primarily as a studio space and Rich intend’s to expand its use to a series of select international projects where visiting artists, curators and researchers can use it as an ad-hoc base of operations while in Vietnam. There is an extensive archive with over 700 books on contemporary art, design, southeast asian history, theory and literature that has already been used by students in these fields.

Read Rich Streitmatter-Tran’s interview here.