ICI’s Alaina Claire Feldman met in New York with 2016 Independent Vision awardee Miguel A. Lopez to discuss his curatorial practice.

—

Photo: Daniela Morales

Alaina Claire Feldman: Much of your work reflects on the framing, classifying, and ordering of contemporary art, on subjectivity and how it informs our experience of the world. When I was looking over your impressive list of projects, one name kept reappearing: Sergio Zevallos, the Peruvian-German queer performance artist, and Groupo Chaclacayo, the group he helped create. I thought we could begin here because Zevallos’ presence in your practice is indicative of your interest in a certain narrative, in an individual practice and also a collective practice. I want to discuss your dedication to a type of art and exhibition making that is about inclusivity, and about accounting for practices that have been marginalized or even suppressed. Where did your interest in this work begin and why?

Miguel A. Lopez: I first heard about Grupo Chaclacayo when I was studying, when I was about 19. It probably came out of a conversation in 2002 or 2003 with my colleague curator Emilio Tarazona, who at that time was researching them. The group included three artists Helmut Psotta (from Germany) and his Peruvian students Raul Avellaneda and Sergio Zevallos) who between 1982 and 1989 had self-exiled outside of the city of Lima to distance themselves from conservative mores and the existing local art system. They were looking for conditions to create and experiment without restrictions. During this period, the work combined sexual and political expressions through a profane visual iconography that dramatized Catholic devotion. They were also using tropes related to the armed conflict in Peru, which began in 1980 when the Maoist organization Shining Path launched a war to overthrow the state. It was astonishing to see the few images of their work that were accessible at this time, and I was fascinated by how little was known about it. Why had it been so difficult to trace this work? Why hadn’t there been an exhibition about their work since the ‘80s? I wasn’t studying art history but I knew that I wanted to dedicate myself to research and writing, so when I had the chance, my artist-friend, Eliana Otta and I contacted Sergio for an interview. Our first conversation with him was around 2004. I remember he was a bit skeptical about our approach, because the Grupo Chaclacayo left Peru in 1989.

ACF: They left Peru and went to Germany?

ML: They moved to Germany in 1989. That same year, Grupo Chaclacayo organized a big exhibition, Images of Death: Peru or the End of the European Dream, that toured to museums in Stuttgart, Bochum, Karlsruhe, and Berlin. They produced new installations and live performances with ritualistic language attempting to connect the colonialism in America, the armed war in Peru, and the fall of Soviet communism. A Peruvian art critic accused them of being associated with said Shinning Path subversive organization, and wrote an article in a Peruvian magazine calling these shows a “shrill and frivolous apology” for Shining Path. The exhibition catalogue included a list of the crimes against human rights committed by military forces in Peru during 1980s, which the critic interpreted as a form of support for this Maoist group. In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, an accusation of terrorism could endanger people’s lives because one could suddenly “disappear” by the armed forces. The group never returned to Peru; it was only after 2000 that Sergio decided to come back to Lima. When I first contacted him, he asked, “Who are you exactly? Why do you want to ask me these questions?” I was part of the editorial board of Prótesis magazine, an independent initiative created by the Catholic University art students. He asked me, “But why do you want to interview me for a magazine from this university? I quit that university!” This scenario gives you an idea of how difficult it was for him to talk about this history.

ACF: He was fearful that Peru and this institution that dismissed him would now try to recuperate his practice several years later.

ML: Although, Prótesis was an independent magazine just using the art department’s money. We published the interview in 2005, and this was one of the very few interviews with him in the 20 years since he left Peru. This interview was important for me because I realized the symbolic threat that these aesthetic practices represented for traditional social values and how they defied the conservative understanding of art and traditional ideas of art education. In 2007, two years after the interview, I was invited to the Württembergischer Kunstverein in Stuttgart, Germany, for a symposium that later became a collective curatorial project entitled Subversive Practices. After Stuttgart, I decided to visit Sergio in Berlin. I asked him to trust me to help him to organize his archive, to recover the history of his work in Grupo Chaclacayo. During the first years I was working with curator Emilio Tarazona, we were both seeking to show the work of the three members of the group, but unfortunately that never happened. After a while Sergio and I decided to work together. It was the beginning of a long process.

ACF: In 2013, your relationship with him finally culminated in an exhibition in Peru.

ML: I wouldn’t call it a culmination but definitely it was the most important presentation of his early artistic production. The exhibition A Wandering Body: Sergio Zevallos in the Grupo Chaclacayo (1982-1994) was exhibited in two venues: the Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) and Spanish Cultural Center. The show presented a comprehensive selection of his drawings, collages, photographs, and performances. The exhibition generated a lot of interest but also a number of hostile reactions; some Catholic religious groups demanded the closure of the show accusing us of blasphemy. Of course MALI rejected that petition and stated their commitment to free speech and respect to the intellectual independence of the artist and curator. This was exciting because our desire was clearly going beyond contemplation and the context of art history. We were seeking to trigger a discussion of the narratives of the war in Peru and to expand debates on what gender and sexuality has to say about our recent past.

.jpg)

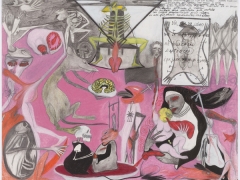

Sergio Zevallos, Untitled, from the series Rosas (Roses), 1982. Charcoal and Color chalk on paper, 69 x 89 cm. Private collection, Lima.

One of the arguments I stressed in the show was that the rejection of their work during the ‘80s was not only because of concerns related to ideas of the best or quality or because of its politically driven practice. It was rejected because such a deeply transgressive homosexual aesthetics represented a threat to the national masculine body’s borders and the way public space was regulated and codified. It is not enough to say that the claim linking the creative practices of Grupo Chaclacayo and the Maoist Shining Path was absurd. The relationship is revealing because this group and their queer sadomasochistic grammars was seen as threatening as the armed raids of a Maoist totalitarian subversive group.

Their work reveals that the armed conflict in Peru cannot be reduced to an ideological struggle driven by communist ideas and attempts to seize power, as some right-wing parties argue. On the contrary, the conflict was a result of an enduring colonial, patriarchal, and heteronormative social structure. The persistent appearance of queer corpses and burials in their performances and photographs draws attention to an unrecognized war: a war declared against homosexual, effeminate, sick or differing bodies, and any body that is not useful for the productive demands of capitalism. Within the war these include of course, predominantly peasant and indigenous communities, and also transgender or queer bodies.

.jpg)

Sergio Zevallos, Ambulantes (Wanderers), from the series Suburbios (Suburbs), 1983. Performers: Frido Martin, Sergio Zevallos and anonymous passer-by. Gelatin silver print on baryta paper, 14 x 9 cm. Museo de Arte de Lima. Contemporary Art Acquisition Committee 2013.

ACF: It was almost as if this revisionist art history was a political strategy of its own, to rethink the socio-political history in Peru.

ML: We wanted to propose questions about how art history was written, but more importantly, we wanted to reintroduce issues that are constantly erased from the conservative, local debate. I firmly believe that museums can contribute to the reconstruction of a democratic public sphere through their critical activity and thus defy some consensual discourses and conservative social structures. But still there is a lot to discuss. After Lima, the exhibition travelled to Württembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart in October 2014, where it fueled more debate. Working with Sergio to make this research project happen was a life-changing experience. It is fascinating how a relationship with an artist can radically change your own perspectives regarding the wider implications of curatorial practice and its political potential.

ACF: And you continued to expand these arguments within two publications about the work.

ML: We made two publications, with the Lima Art Museum (2014) and also with Proyecto AMIL (2015). The first book included more than three hundred and fifty images from his archive. It had newly commissioned essays, newspaper clippings, and interviews from the 80s and 90s, previously unpublished documentation of performances and sketches of the actions, and precise information about the projects they developed. The second publication focused on Sergio’s drawings from 1982 to 1987. I like to conceive books as a toolbox for research. We wanted to make the documents we encountered as accessible as possible so that other people can continue to push these discussions and research further.

ACF: Typically, an exhibition is only on view in one place for a certain period of time, while the publication is what lives on and builds a memory of the project. Is Sergio still practicing in Germany?

ML: He is still active, living between Germany and Peru.

ACF: The work was initially generated to respond to a very specific political regime and the kind of violence it created for Sergio and his community in Peru. But how is this relevant to his current work? Is he still thinking through Peruvian history; is he thinking about Europe, or both?

ML: He moved to Germany in 1989, so much of his life now relates to Europe. His recent work is still concerned with the mechanisms of how repression operates and with contemporary models of governance in which bodily and sexuality issues play an important role. I think the way we returned to that early period gave him new perspectives and ways to continue his creative work. Sergio will produce a new work for the upcoming documenta 14. It’s exciting to see how his work is starting to receive the recognition that it deserves.

Red Conceptualismos del Sur

ACF: I want to ask you about the beginnings of the group that you cofounded, Red Conceptualismos del Sur (RCS). This is another long-term, collective commitment to reshape history through decentralizing a narrative of contemporary art.

ML: In 2007, a group of six people, including myself, cofounded RCS. We met each other through our common interests in political narratives about Latin American art and our shared concerns about the uncertain fate of important art archives in our region. Each of us each has our own version of this story, but my involvement began when I met art historian and writer Ana Longoni in Buenos Aires in August 2006. At that moment I was immersed in research about experimental practices in Peru during the ‘60s and ‘70s and found her essays and books on ‘60s avant-garde practices in Argentina encouraging and inspiring. I remember receiving payment from my first curatorial project earlier in 2006 and I used all the money to fly to Buenos Aires to meet her. Meeting Ana changed my understanding of art history as a framework for passionate commitment and political engagement. We didn’t talk about creating a group at the time, but rather about how important it was to have exchanges with colleagues doing similar research. In 2007, Ana was invited to contribute to a seminar at the MACBA in Barcelona, organized by Spanish artist Antoni Mercader. She invited myself and other Latin American researchers and art historians to get involved in the public activities, which was when we founded the network. RCS now includes more than fifty researchers, art historians, writers, and activists from different places; the network grew quickly. I remember our first conversations were about Latin American conceptual art being in fashion.

Installation view of Losing the Human Form. A seismic image of the 1980’s in Latin America, curated by Southern Conceptualisms Network, at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, October 2012 – March 2013. Photo by Román Lores and Joaquín Cortés. Courtesy Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.

ACF: Do you mean economically?

ML: Yes, economically. We were worried that new market demands could bar the process of recuperating a constellation of experimental art practices developed under conditions of conflict, dictatorial regimes, and civil war. For us, contributing to the reactivation of these radical legacies implied not only politically positioned writing or researching these artistic experiences, but it also required questioning: How to generate conditions for the conservation of these materials in our own contexts? This was a very delicate situation in countries where artistic communities distrusted the existing governmental institutions because of their authoritarian and repressive past. We were worried that these materials would be lost. We felt that it was quite important to intervene in order to prevent the danger of dispossession and the physical loss of art documents. So we started thinking about how to trigger a larger discussion around the urgency to implement strategic responses and how to take collective responsibility for the care of material patrimony while involving local institutions.

ACF: These materials and discussions would then be expanded pan-continentally among your different contexts.

ML: We wanted to collaborate with museums and universities to create public archives, or loans for these archives, to move artists’ archives to the institution and give the public access to them. Since 2008, RCS has worked on several archives of artists whose work was fiercely positioned against military dictatorships during the ‘70s and ‘80s, such as the archive of the Uruguayan poet and artist Clement Padín that was transferred to the Universidad de la República in Montevideo, Uruguay; or the archive of the Chilean activist-artist collective CADA (Colectivo de Acciones de Arte) that was moved to the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, and which will later be donated to the Museo National de Bellas Artes in Santiago de Chile. We are doing the same with the archives of artists Francisco Mariotti and María Luy, which document important experimental and collective experiences from the ‘70s in Peru. Those materials are traveling from Switzerland to the library of MALI in the next few months. Some manifestos and public projects that we recovered from this period, including part of Projecto Helio Oiticica’s holdings in Rio de Janeiro which were mostly destroyed by a fire in 2009 or the ICAA digital archive of Latin American and Latino Art at the Museum of Fine Arts of Houston, have recently gained attention and helped to create a sort of “archival momentum” (as art historian Andrea Giunta called in a 2011 symposium).

Even if we couldn’t perceive it at the time, we were helping in shifting the value of critical artistic practices within Latin American institutions. That situation changed not only the social status of those documents, but also their economic value. The deferred effects of a project such as Global Conceptualism (1999) as well of some curatorial and scholarly initiatives focused on the ‘60s and ‘70s in Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Peru during those years galvanized the desire to tackle metropolitan narratives and remap a set of priorities that, up until then, organized the institutional policies of collecting and preservation. Consider that ten years ago, in 2007, when we push these discussions, the landscape was very different. Museums in Latin America weren’t precisely interested in shaping the local memory through archives; many were hesitant to acknowledge that this scarce documentation could actually represent an opportunity to complicate notions of education, access, collecting and exhibition-making. There were only a few archive initiatives—such as Fundación Espigas or Archivo Jorge Romero Brest, both in Buenos Aires—that were introduced years earlier by the needs of scholarly activity unburdened by the pressures of the art market. Today, such policies now exist in large museums in the region, such as Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) in Mexico City or MALI in Lima, which are actively acquiring and incorporating archives with the clear understanding of its public effects. I can’t help thinking that the consequences of RCS’s discussions about archives, accessing, and conservation, has something to do with this change.

Conceptualismos do Sul/Sur (Conceptualisms of the South). First International Symposium. Sao Paulo, Museu de Arte Contemporãnea da Universidade de São Paulo, April 2008.

ACF: How does the collective dimension of RCS function?

ML: Our network operates in a very decentralized way. RCS is articulated by working groups who decide collectively on what to research, how to make it public, how to take positions on specific situations, and what strategies to develop for sharing information and fundraising. It’s quite organic, an open conversation centered on the desire for alternative historiographic production. The collective aspect of our work is relevant because our endeavors demand active involvement and are situated analyses that usually go beyond the limits of individualistic modes of working. The collective dimension is also important for strategic alliances based on trust to create a dialogue between the material memory of underground practices and its agents and more formal institutions. Diving into the archives and patiently recovering forgotten material gives rise to a different way to conceptualize an exhibition, one in which weaving narratives doesn’t depend on conventional categories or established art figures. An example of this is the exhibition Losing the Human Form. A Seismic Image of the 1980s in Latin America, a reading of the ‘80s through the lens of creative social disobedience that we curated at the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid in 2012. The project, which was also exhibited in Lima and Buenos Aires between 2013 and 2014, presented a panorama of experimentation and resistance focusing on the visual politics of social movements (like Madres de Plaza de Mayo in Argentina and Mujeres por la Vida in Chile), dissident sexual practices and queer art collectives, and underground scenes. Most of the exhibited materials were graphic pieces, videos, mail art documentation, silk screens, photographs, installations and other fragile traces associated with those activist practices. A project like this—including more than three hundred objects, many of which had never been shown before—was only possible because this specific project was comprised of more than thirty-five researchers working together to create a dialogue alongside our research.

Collaborative work, or collective curating in this case, is important for me because it offers a possibility to go against the increasing presence of the curator-as-celebrity, and the prevalent ideas of success as defined by the global art market. As my friend Julia Bryan-Wilson points out, we as curators and cultural agents have to be aware of how we circulate within frameworks of power. How are our practices contributing to the dominance of economic spheres over life and cultural activity? In what ways can we be tactic in inventing forms to interrupt this logic?

ACF: The concept of the individual has long been privileged over that of the collective. Sure, it’s easier to capitalize on individual recognition for professional and economic reasons, but doing art history is a collective exercise, nuanced and dynamic. And curating collectively is a way to undermine existing normative systems of historiography. What I find exciting is that RCS is decentralizing information geographically but also employing a transdisciplinary approach as art practices and exhibitions become politics, which become social history. What kinds of direct reactions are you hoping for?

ML: I hope the work decentralizes a debate around institutional policies. I’m constantly observing the types of narratives being produced in Latin American art institutions. We’ve taken a big step forward from the previous decade, but there are still many things that are not discussed: for example, the politics of representation of female artists in institutions, where a gender imbalance is so insistently present. If you look at a schedule of exhibitions, you will see that men have a higher percentage of solo shows at major museums. When I mention this, some people think that I’m invoking an essentialist argument. I wish this was the case, but the issue is far more complex than that. Look at MALI in Lima, one of the most progressive museums in the region: Since 2010, they presented more than twenty-five solo shows, and only one exhibition was by a female artist. But the most problematic aspect is that this disparity is normalized. This is why a program dedicated to recognizing and creating value around female artists, like the one that Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA) launched in 2015, is so important. What are the social effects of a museum that only exhibits male artists and reinforces a patriarchal model of the public sphere? Museums are political devices that produce social identities and shape subjectivity. It is the same struggle in regards to collecting. You have to create really strong arguments to push the inclusion of women artists, queer aesthetics, black and indigenous representations…

ACF: You have to defend the relevancy of the work to those who may not be familiar with the artist, and cultivate a sort of public knowledge.

ML: But it’s not only about knowing or not knowing the artist. It is the structure of valorization that prevails, which exists historically to reinforce white, male, western privilege. In most instances, the valorization of these art practices weren’t fully created yet. Collecting is complicated because it is clearly based on the demands of the market. Still, we need to insist that collections in Latin American institutions address issues that are being erased. If we don’t have in these collections specific works dealing with HIV for example…

ACF: …then those issues and works that consider those issues are erased from history.

ML: Exactly. And I’m not saying that these debates need formal institution to exist; feminist collectives and queer activism have been always ahead creating autonomous spaces for thought and resistance for decades. What I mean is that it is also extremely important to have discussions in cultural institutions and museums and reflect, in another scale, how visual representations became spaces of grief, loss, rage and public fighting against homophobia and racism. Most of these works are not flashy, they use unfamiliar aesthetics tropes and not are very well preserved, but they can certainly push political discussions in a different direction. And that is why the role of the curator is so crucial. We need politically situated curatorial practices that take responsibility for class privilege and cultural capital and do the work of create cultural value against the dominant male culture, social inequality and discrimination.

TEOR/éTica

ACF: You recently joined TEOR/éTica in San José, Costa Rica.

ML: I was appointed in March 2015 and I moved to Costa in late-May that year.

ACF: Is this your first “institutional” job?

ML: Yes, my first. After a decade working as independent curator, I thought that maybe it was time for me to join an institution and commit to art history in a different way—by building infrastructure. I couldn’t imagine a better job and place to work.

ACF: TEOR/éTica has a fantastic history and draws an audience that really respects it. Viewers go there to be challenged.

ML: We have an enormous responsibility because TEOR/éTica is one of the most active organizations in the region. The institution was founded in 1999 by Virginia Perez-Ratton, a Costa Rican artist and curator. Its mission is to contribute to the research and diffusion of contemporary art practices in Central America and the Caribbean in dialogue with global realities. TEOR/éTica helped to create more visibility for regional art practices which did not fit within the traditional hegemonic narratives of Latin American Art that, until the 90s, largely excluded the region.

ACF: European and American art historians and curators, who typically only looked at Brazil, Mexico, or Argentina as “Latin America”, also influenced those narratives.

ML: Exactly. Virginia Perez-Ratton founded TEOR/éTica to contend with that. Now, of course, the panorama has changed; it’s not the ‘90s anymore. But there is still a lot of work to be done in promoting artistic and critical practices from Central America and the Caribbean. For example, I would expect local universities to be more involved in producing publications, encouraging historical research, introducing experimental ways of thinking about art education, and creating international seminars to discuss the relevance of contemporary art in society—but unfortunately, this is not the case.

ACF: Expecting universities and schools to be more involved in their local art communities and promoting critical practices seems like a given, but I hear from colleagues everywhere that this is not the case. Perhaps this lack of involvement is indicative of a larger neoliberal shift. When governments cut education budgets, it is always art, music, or liberal studies that become reduced first. Therefore, people visit museums and art spaces expecting to have these educational gaps filled. They are trying to compensate for a void in the educational sphere, which, for a number of reasons, the government feels is no longer their responsibility. You are currently mobilizing a series of public activities and publishing projects for TEOR/éTica—that has always been a tradition of the foundation. But are you excited to create any new agendas?

ML: We are in the middle of a process that has been very revealing for all of the members of TEOR/éTica. Our aim is to transform the institution into a more accessible and dynamic entity. We are enquiring our ways “of doing”, disputing the centrality of exhibitions within the program and the relationship we have to our immediate context. So we started questioning the idea of directorship and the figure of the curator in order to mobilize a more collective dynamic in decision-making. One of the most important decisions during this recent process was to not host any art exhibitions during 2017, at least not in the way we were previously. The idea is to use all of our spaces in different ways, placing research, conversational dynamics and spontaneity at the forefront. We know that there is going to be some trouble because we are reimagining the whole structure, but we are very excited of this new moment. The most interesting aspect of this is perhaps its unpredictability; the only thing we know now is that we are going to change. It is a real experiment.

In part, this is an oblique effect of our interaction with Arts Collaboratory, an ecosystem of more than twenty art organizations around the world that we are part of, which helped us to reimagine the life of our institution based on concepts such as self-care, self-limitation, and commonality. But mainly is a response to the fatigue of always doing the same and the bureaucratization of daily life. There are some dynamics developed at TEOR/éTica in 2016 that we would like expand, like the Alter Academia, conceived by researcher and curator Maria Paola Malavasi, which was an experience that opened up some new possibilities to envision our relation with local art community, artistic process and education. The project consisted of four artists –in-residence using TEOR/éTica’s exhibition spaces as studio for three months so that the artists could develop research projects and dialogues between them and with visiting scholars, architects, thinkers or scientists who were periodically invited.

Intervention Shape of Freedom by Carlos Motta at TEOR/éTica’s façade, 2015. Installation view at “Read My Lips.” Photo: Daniela Morales.

ACF: Was it open to the public too?

ML: The artists could invite whomever they wanted to their space at any time, and there were also some instances when engagements were totally public and everybody was invited to visit. It worked very well because the program didn’t demand the production of an object or a show. It created the conditions for conversation, which involved in different levels many people from TEOR/éTica. The important thing for us was the way they actually occupied the institution. During that time, they transformed the way we perceived TEOR/éTica, forcing us to questioning our own positions. In 2017 the plan is to continue with the Alter Academia and to develop a second edition of the program. There is another new project leaded by writer Paula Piedra in collaboration with Proyecto Semillas, an interdisciplinary group that promotes community social architecture and co-manage