Leeza Ahmady in the Bagh-e-Babur gardens, Kabul, February 2012.

After countless years, I went back to Kabul Afghanistan on two different occasions in 2012, unexpectedly through my role as a dOCUMENTA (13) Agent. Both instances proved to be exceptionally moving experiences, especially connecting with those making waves, and those trying to advance the country’s artistic communities.

To better convey my intentions for this edition of ICI Dispatch, I will start by rephrasing a short excerpt from my recent interview with Art 21: Inside the Artist’s Studio.

Public education is a key component for all my work. It begins with self-education. A process of un-learning what’s been acquired through conventional study, collective mentalities, societal roles, etc. The task of maturity is to navigate through that jungle of “dead information” in our minds daily. This practice is known as consciousness. In other words, developing an internal muscle for discriminating information, the way we receive and digest food. This leads not merely to knowledge, but perhaps more importantly, to wisdom. I am therefore, not interested in positioning my own expertise, or those of others through this report, but rather in creating both a personal and professional outlet for inquiry. Ways of accounting, and confronting inertia, as well as ignorance about very compelling, unexplored, subjects in contemporary life, art, and history.

Left: King Amanullah and Queen Soraya (1919-1920) from a limited edition photography book, Images of Afghanistan 1838-1921. Right: Fire, Dar ul-Aman, 1968, from Mariam & Ashraf Ghani, Afghanistan: A Lexicon dOCUMENTA (13) Notebook, 2012.

Art in Kabul as in many places in the world exists in complex layers of parallel and crisscrossing lines, in often-disjointed scenes. I wish to convey this dynamism to rewire our thinking patterns in regards to so-called “troubled nations”, whose collective imagery is forever scarred by constant, relentless speculation and manipulations of popular media channels, governments, and other control agencies worldwide. Everyday I woke up shocked by how normal life was in Kabul. Facing my deeply imbedded fears re-enforced by years of negative reports on the country. Having always imagined myself in possession of an impenetrable mind, I had to re-examine the landscape of my own subconscious, pulling out weeds still plugged into some sort of centralized info-station or another.

Indeed most reports on Afghanistan both inside and outside of the country primarily focus on military, policy, and politics related to war, conflict, and terrorism. When art or culture is the focal point, it is slanted towards issues of repression, trauma, and a lack of cultural freedom. Yet there is an encouraging group of artists working, and scenes forming throughout Kabul and other select parts of the country. Like artists elsewhere, many manage to sublimate circumstantial conditions through their own individual resilience, hope, creativity, perseverance, invention, and love for art. This Dispatch is dedicated to such efforts.

Left: Bagh-e Babur under the snow, courtesy of AhmadyArts, Afghanistan, 2012. Right: Photograph of Kabul, courtesy of AhmadyArts, Afghanistan, 2012.

My first trip was to a snow covered Kabul in February for a series of seminars and workshops involving international and diaspora artists, art writers, curators, thinkers and historians, organized in partnership with several Afghan public cultural institutions active in different fields such as visual arts, music, theater, and film. Over the course of a month I participated in several seminars and workshops and presented alongside colleagues to engage a select group of young Afghan artists and students of art, theatre and literature. A whirlwind experience, we explored modes of thinking about art, creativity, time, and consciousness, both historical and contemporary; addressing also surfacing questions as a result of such discussions.

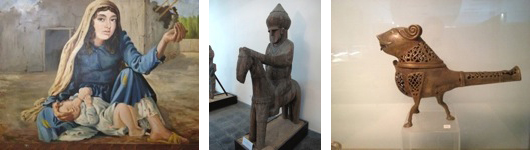

Left: Muhammad Yosuf Kohzad, oil painting, c.1960s, National Gallery of Art of Afghanistan, Kabul, Afghanistan. Middle: Wooden carved statue from Kafiristan or the “Land of the Infidels,” now known as Nuristan, region of Afghanistan, c. mid-1800s, National Museum of Afghanistan, Kabul, Afghanistan. Right: Animal-inspired bronze oil burner belonging to Ghazni archeological site, 12th Century AD, National Museum of Afghanistan, Kabul, Afghanistan.

“When can we say an artwork is contemporary? Does an artwork need to be explained? What are the various instruments for expressing what an artwork is?” These are just some examples of the many essential questions raised by participants. The second trip was for the much anticipated, much speculated, and wholly invigorating June opening of the dOCUMENTA (13) exhibition at the Bagh-e-Babur Gardens in Kabul. A superb coming together of local, diaspora, and international artists, it was not without its problems and challenges, but will always represent an important historical gesture in collaborative dialogue about contemporary art and its role in individual lives, and society at large.

Top left: dOCUMENTA (13) Exhibition Opening Ceremony, Kabul, Afghanistan, June 2012. Top right: Opening Ceremony Talks, dOCUMENTA (13) exhibition, Kabul, Afghanistan, June 20, 2012. Bottom left: Caroline Christov-Bakargiev and translator Khan M. Atebari, Art Histories in the Forms of Notes seminar, as part of dOCUMENTA (13) Seminar Series, Kabul, Afghanistan, February 4th, 2012. Bottom right: Jeanno Gaussi, Peraan-e-Tombaan, Military insignia sewn onto traditional Afghan men’s clothes, Installation, dOCUMENTA (13) exhibition, Kabul Afghanistan, 2012.

This introductory text is an overview of general impressions and reflections about Kabul, the city, the country, artists, artworks, projects, people, and places. It is accompanied by images that tell a good many tales on their own. In upcoming posts, I hope to add more content about select artists and cultural situations in the country, as well as expand on program details, insights, and afterthoughts about the seminars, workshops, and exhibition initiated by dOCUMENTA (13) in Kabul and Bamyan, Afghanistan, February thru July 2012.

Top left: Aman Mojadidi, Memories Are Not Related, Installation of photographs and video stills, dOCUMENTA (13) exhibition, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012. Top right: Michael Rakowitz, What Dust Will Rise?, Installation, dOCUMENTA (13) exhibition, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012. Bottom left: Barmak Akram, Phytomorphismes, 2012, Paper (cuttings), Installation, dOCUMENTA (13) exhibition, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012. Bottom right: Giuseppe Penone, Roots of Stone, Marble Stone, Permanent site specific sculpture, dOCUMENTA (13) exhibition, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012.

There are no maps that pin down where art establishment are located in Kabul. In fact, I rarely knew where I was going until I arrived. Hopping into hired cars, I found myself weaving in and out of military zones, government zones, residential clusters, pockets of foreign and expat frenzy neighborhoods, hotels, restaurants, embassies, schools, shopping malls, wedding halls and so on. Each separated and sectioned off in endless mazes of concrete walls, checkpoints, and surveillance towers. It seemed unlikely that behind some of those enclosures I would encounter gathering places for creative collectives, art centers, community theaters, artists studios, workshops and art classes. These places cannot be found on one’s own; you do not simply stumble across a gallery on a stroll. Good art is a hermetic practice everywhere; one must be consciously willing to look, and do so beyond external facades both mental and physical.

Left: Artist and filmmaker Barmak Akram, detail of a piece from the seminar Acts, Gestures, Things, and Processes: Material and Performances, as part of Kabul/Bamiyan dOCUMENTA (13) Seminars, workshop focused on performance and sculptural material, working with ceramics, Institut Français d’Afghanistan in Istalif, Afghanistan, April 15-20, 2012. Middle: Ommolbanin Shamsia Hassani, Graffiti Project on the façade of the former Russian cultural center, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2011. Right: Ruins of the former Russian cultural center from the 1980s, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012.

Thus, the arts infrastructure, if one were to apply such an institutionalized term for describing Kabul’s art scene, is nonexistent. Yet looking through another kind of lens, one that is very specific to the here and now of Afghanistan, one does see traces of a shape not entirely defined, yet discernible.

In manners much like the country’s age-old oral-storytelling traditions, one artist guided me to another, one organization to another. At times through unconscious expressions, complaints, and riff-raffs common in all art communities, large or small. Others who led me to much discovery were in-member groups of locals, expats, and internationals, knowledgeable and frequenting various hot spots, some of which are close, but still disengaged from each other. These disconnections are not only due to segmented nature of Kabul as a city today, deemed necessary for security purposes, but also by unfortunate prevailing classicisms that still mark its society, indeed very profoundly.

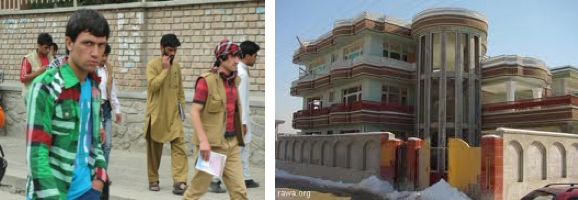

A city I couldn’t quite recognize anymore. As a child living there, I remember open circular roads giving way to rectangular neighborhoods like a lovely tune on an accordion, now muffled by concrete everywhere, the harmony still attempting to resonate despite massive expansion of its quarters in all directions. A city losing its architectural integrity to cheap glass buildings that rust even before completion, overwhelmed by what Kabul natives contemptuously call: “Wedding Cake Houses” appearing indiscriminately everywhere. These are brightly colored, multi-floored, and terrace-layered facades bulging over streets, ludicrously disproportionate to the properties they occupy.

Left: Students coming out of Kabul University, Kabul, Afghanistan, June 2012. Right: A “Birthday/Wedding Cake” house in Kabul, Afghanistan, Light and Shadow blog, 2012.

Many such spectacles are fast replacing what is remaining of great old neighborhoods once lined with quintessentially modern style homes mostly built in the 1950’s, 60’s and 70’s. Minimalist and modular in shape, constructed mainly of a beloved mixture of local materials: mud, clay, and hay. A fabulous concoction known as Ka Gill that I loved to jump into, before every other winter, when we used it to re-enforce our roof against the coming snow.

Both trips were emotionally intense and very energizing, confirming that artistic, intellectual and cultural knowledge is being dispersed more and more readily within Afghanistan, by and for Afghan and international partners alike. I have been asked, “Why is this happening now?” I believe that the arts are a society’s most deliberate and complex means of communication, and artists and those who work in the arts help communities constructively engage with long histories of trauma, reciprocal distrust, insularity, and conflict. None of what I am about to highlight below has come about overnight. It is naive to believe so. Many of the artists have developed and evolved their works over a long time, expanding on region specific traditional fine arts and philosophies, as well as modern art practices and critical trajectories prevalent in the 20th century, worldwide.

Left: Turquoise Mountain Studio Visit, Kabul, Afganistan, 2012. Right: Khadim Ali’s miniature workshop at the Turquoise Mountain Studio, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012.

There are more women enrolled in academic art and studio programs than men (based on Department of Fine Arts enrollments in Kabul and Herat Universities). Art, theatre, and music events are regularly presented at public institutions or makeshift venues such as private homes, NGO spaces, embassies, etc. Experimental theatre companies have gained incredible momentum, inspiring initiatives such as AHRDO; an all-Afghan led and run civil society organization that uses participatory theater to promote human rights, accountability, and democracy throughout the country by focusing on personal and collective narratives.

Left: A group of young artists, Center for Contemporary Arts Afghanistan (CCAA), Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012. Right: Members of the Association of Beautiful Fine Arts Writers and Calligraphers of Afghanistan, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012.

Traditional fine arts such as miniature painting and calligraphy boast established associations in Kabul, Herart, and Mazaar, and other parts of the country. Visual artists of all generations experiment with miniature and calligraphy art but many also engage in hybrid painting styles: Surrealism, Cubism, Realism, and Abstract Expressionism. Young artist associations such as Roshd Group have turned to other outlets for expression, like graffiti on the walls of abandoned ruined sites. For example, the Russian Cultural Center in Kabul. Jump Cuts, a young filmmakers collective, are experimenting with “poetics of imagery” in their short films, some of which have entered international festivals.

Top left: Artwork by faculty member/director of Department of Fine Arts, Kabul University, Afghanistan, 2012. Top middle: Sher Ali, Untitled Installation, date unknown. Top right: Studio visit with a faculty member, Department of Fine Arts, Kabul University, Afghanistan, 2012. Bottom left: Studio visit with a faculty member, Department of Fine Arts, Kabul University, Afghanistan, 2012. Bottom middle: Kabir Mokamel, Companions of the Elephant, Oil on canvas, 2010. Bottom right: Kabir Mokamel, Dead British Soldiers, Superimposed photographs, 2011.

“Safe haven”-type spaces have sprouted with many creative endeavors in the fields of preservation, education, archiving, public programming, contemporary art, and design. A leader on this front is the Center for Contemporary Art Afghanistan (CCAA). Since its establishment in 2004, CCAA has been providing visual artists with resources for art practice and a deeper understanding of the creation process through classes, seminars, and projects in various mediums (painting, video, photography). However, CCAA programs have faced some major setbacks in recent years due to demands by its European and US-based funding partners, limiting CCAA to focus exclusively on projects involving painting classes for women.

Left and right: Zalmai, Ghost War – Playing with Empires, 2011, Photographs, Commissioned by dOCUMENTA (13).

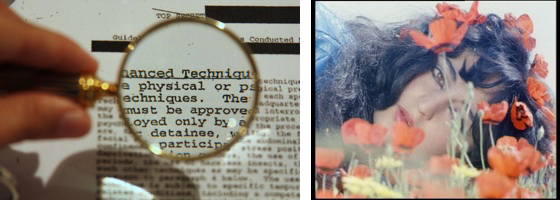

Many artists have returned. Some live and work in between Afghanistan and the Middle East, Europe and the United States. A standout photographer, Zalmai’s artistic perspective is one of harsh realities; the life of Afghans in a land still occupied, and conflicted, are softened by his extraordinary agility to arrest monumental beauty in every one of his shots. Diligent and multifaceted artist, writer, and educator Mariam Ghani has been conceptualizing and shooting material for her videos and installations in Kabul since 2003, many of which launch quiet investigations of slippery situations (i.e. re-hiring of Afghan-Americans who had previously worked as translators for the US military in Afghanistan to translate documents related to US military prisons in Afghanistan. Entitled “The Trespassers” and commissioned by Sharjah Biennial X, 2011). Through her dOCUMENTA (13) workshop ‘Archive Practicum’ Ghani and her selected team collaborated with Afghan Films, the national film institute of Afghanistan to initiate a digital film archive. Their efforts have already seen 90 or so films digitized, ranging from the 1920’s to the 1990’s, and cutting across many genres including newsreel, documentary and fiction features.

Left: Mariam Ghani, The Trespassers, Film still, installation with HD video projection, 4-channel sound, 2010-2011. Right: Epic of Love, by Engineer Latif Ahmady, 1984, as part of the seminar Archive Practicum led by Mariam Ghani and Pad.ma who worked with the Afghan film Archive team to choose and digitize selected reels from the archive, dOCUMENTA (13) seminars, held at Afghan Film archive, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012.

Designers Raheem Walizada and Zolaykha Sherzad operate unique studio practices that also contribute to the economy of the Afghan creative industry. Walizada merges an unrelenting multiplicity of traditional Afghan motifs with his own magical sense of aesthetics, applying age-old Afghan techniques to create stunning rugs, furniture, and architectural projects, coveted both inside and outside the country. At Zarif Design located in Sharenow, Kabul, 75 master and apprentice tailors and artisans (men and women) come together under the direction of Sherzad to design arresting textiles, elegant clothing, and more. All are inspired by and surpass traditional Afghan and Central Asian textile-arts and fashions. Organizations such as the Aga Khan Foundation are restoring important cultural sites throughout Afghanistan, such as the newly restored ruins and grounds of the Bagh-e-Babur, Kabul.

Left: Designer Zolaykha Sherzad at her studio boutique and workshop, Zarif Design, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012. Middle: Zarif Design, workshop artisans embroidering, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012. Right: Designer Rahim Walizada in his studio, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012.

This is just a small sampling of the rich initiatives in Afghanistan. Unfortunately, not only are these projects almost entirely unknown internationally, but also even locally there are no mechanisms for awareness and communication, leaving organizations disconnected from each other and their audiences. One of the greatest needs to nurture the arts is to promote deeper awareness among individuals and organizations throughout the country, and in effect tie the community into a more cohesive, collaborative group.

Left: Electronic music event in an anonymous space, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012. Right: Second annual classical music concert given by Afghan youth playing Ravel’s Bolero, French Cultural Institute, Kabul, Afghanistan, Feb. 2012.

Special Thanks

My Heartfelt Thanks to Astrid Parenty and Sarah Schloemer AhmadyArts, Curatorial Assistants for their great work and efforts towards this report/ organization of images, etc.