In 2016, ICI developed a new program, the Curatorial Seminar, designed to bring mid-career curators together to expand their thinking and advance new areas in curatorial discourse. Geared towards past participants of the Curatorial Intensive, the Seminar offers curators from around the world an unparalleled platform of exchange and discussion, and the opportunity to connect with other curators who share their concerns and research interests. This new program will further energize and leverage ICI’s dynamic network of Curatorial Intensive alumni that has grown to encompass 400 curators from more than 65 countries, bringing unique perspectives to the current evolution of curatorial discourse and practice.

Curatorial Intensive alum Eszter Szakács authored this text, following her experience during the Curatorial Seminar in Marrakech (February 28–March 1, 2016).

Participants included: Mohamed Kamal Elshahed (Cairo, Egypt), Fatima-Zahra Lakrissa (Marrakech, Morocco), Salma Lahlou (Marrakech, Morocco), Eszter Szakacs (Budapest, Hungary), and Ipek Ulusoy (Dubai, UAE). Discussion leaders included: María del Carmen Carrión (Director of Public Programs & Research, ICI), Julian Myers-Szupinska (Associate Professor of Curatorial Practice, CCA and Senior Editor, The Exhibitionist), Renaud Proch (Executive Director, ICI).

—

Unofficial Art and Positive Forms of Resistance Today in Hungary

In 1969, Victor Vasarely’s large-scale retrospective exhibition opened at the Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle, Budapest, for which the artist himself also traveled to Hungary. Vasarely—who was born in 1906 as Győző Vásárhelyi in Pécs, Hungary—emigrated in the 1930s to France where he was at the forefront of creating the movement of Op art. A parallel event was also carried out at the opening of this very Vasarely exhibition in 1969 in Budapest: Hungarian artist János Major (1934–2008) hid in his inner pocket and showed his acquaintances at the inauguration a small sign that read “Vasarely, go home.”1

Why did this symbolic protest take place against the highly renowned artist and his exhibition in Hungary? While Vasarely became world famous, it is also pointed out today that by the end of the 1960s-1970s, his works were no longer viewed as revolutionary.2 Consequently, the invitation of Vasarely in 1969 by the Hungarian political establishment was not only anachronous in this sense, but was also a very peculiar move that directs us back to complex questions of cultural policy in Hungary, a member of the Eastern Block in the Cold War era, where the state is the fundamental sponsor of the arts.

Cultural policy in the Kádár era (1956–1988) in Hungary centred around three principles: initiations were either supported (commissioned, funded, propagated), or tolerated (not provided funding and/or venue), or prohibited by the totalitarian state. While the borders of these three categories shifted and even conflated over time, they divided the cultural sphere into the coexisting “official” and “unofficial” scenes, which inherently meant a relation to the state as well. Synonyms for “unofficial art” frequently include within a Hungarian/Eastern European/post-communist context the similarly elusive concepts of underground or progressive art, Neo-avant-garde art, independent or alternative scene, as well as second publicity/second public sphere (in German: zweite Öffentlichkeit).3 In Hungarian, the very notion of “publicity,” “publicness,” or the public sphere (nyilvánosság) connects to the reclaiming or the subversive use of space, of making things public in art production still today is very much tied to this era. As curator-researcher Zsuzsa László underlined, however, the distinction between the official and the unofficial was made not solely on ideological grounds; it was dependent rather on the interests of those in power.4 Curator and writer Jelena Vesić likewise challenged “simplistic and clichéd” binaries given in art historical narratives of pre-1989 Eastern European art, such as official art (“art considered to develop in accordance with the dictates or at least support of the state”) and alternative art (understood as standing in direct contrast with the sate, ‘hiding’ in dark alternative spaces, artists’ apartments, or in nature, far away from the eyes of the “general public”).5 Consequently, the division between the official and the unofficial was part of a complicated system, rather than a creation of a simple opposition—to which Vasarely’s retrospective exhibition in Budapest in 1969 also attests.

Poster of Victory Vasarely’s exhibition at the Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle, Budapest, 1969

Vasarely, an abstract artist, was thus given the most representative official art space in Hungary, the Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle, at a time when Abstract art—regarded also as a token of the “West”—was banned and not recognized by the state as part of the official art scene. The logic behind such a move, as art historian Edit Sasvári points out, was not more tolerance, but as Vasarely was considered a risk free, “acceptable face of Western modernism” and was also well-known in Hungary, his invitation pertained to a complex political project in the second half of the 1960s of integrating into the local canon Hungarian-born artists who made their careers in Western Europe.6 The Hungarian regime’s “cultural repatriation” of Vasarely—who likewise received at that time an honorary membership and soon two museums dedicated to him in Hungary, and who himself also sought relations with Hungary, for his own reasons—also connected, among others, to the state’s promotional image-building efforts in the West, catered towards to the numerous Hungarian exiles living abroad as well.7 It is no wonder that the story of Vasarely in Hungary, which is further expanded with the anecdote of János Major’s undocumented protest action, was taken as a point of departure in the Vasarely Go Home exhibition project by Austrian artist of Hungarian descent Andreas Fogarasi, who himself is interested in general how politics deplores art and culture.8 Similarly to the dual focus of Fogarasi’s project, some of the current art historical and curatorial research into pre-1989 Eastern European art also highlight the importance of looking at both the official and the unofficial art scenes, as well as their interplay, instead of previous endeavors’ attention to (reconstructing) the unofficial art scene in socialist Hungary and Eastern Europe.9

In contemporary Hungary, while the main funding of the arts still comes from the state, and a small but increasing private or individual sponsorship is present, a newly formed dissent towards the state—and hence a much more pronounced division than in the 1990s or early 2000s—is tacit in the local contemporary art scene. Since the current Fidesz government took to power in 2010, their actions can be characterized by, to a various degree but not unlike other right-wing powers and tendencies today within and outside of the European Union: authoritarian policies, centralization, abuse of power, corruption, anti-intellectualism, xenophobia, nationalism, or historical revisionism. In terms of the arts and the emergence of a (polarizing) cultural policy, a new dominating institution was established in 2011, the so-called Hungarian of Academy of Arts (MMA). It was formerly, since the early 1990s, only a private association of conservative artists, but was pronounced a public body as the Hungarian Parliament passed it into law.10 While an outstanding concentration of state funding, the ownership of a few highly prestigious public assets were transferred to the Hungarian of Academy of Arts—the ownership of the Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle being one of them—and as it now presides over almost all of the allocation of state funds for the arts, the Academy has not yet been able to exert a serious or cohesive program.11 Likewise, already existing (e.g., Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art Budapest) or recently re-named or re-purposed (e.g., the Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center) continue to do work. While there are a few, usually smaller-scale state funded institutions (e.g., the Kassák Museum) which are still able to run a critical program that can also be contextualized within the international contemporary art world, the most prestigious state-funded art institutions operate more on ideology and party politics. Appointing directors and looking over institutional programs and missions have always been a question of politics, since 1989, however, it is the lack of concern for—again, internationally understood—professional criteria.

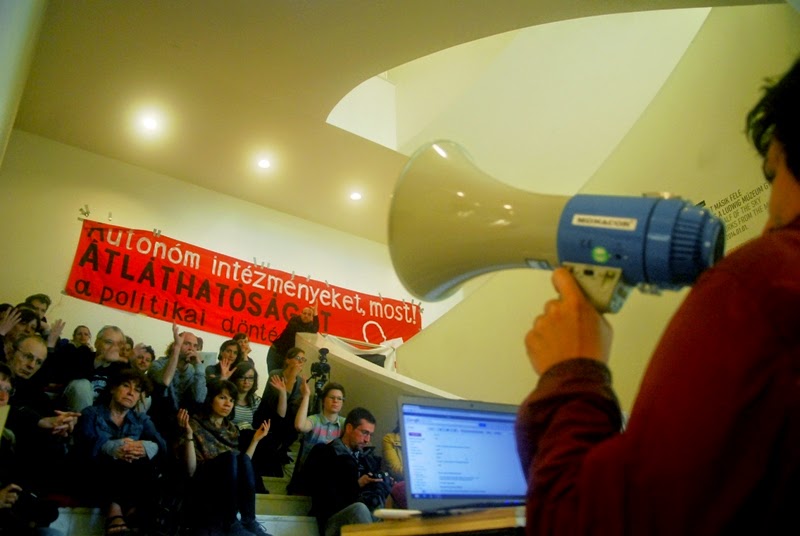

Beginning from around 2012, the first responses of members of the local art scene—who oppose the curtailing of art’s institutional infrastructure that has been (re)built up in the last 25 years, and who do not support the agenda of the Hungarian of Academy of Arts—were demonstrations, protests, or civil disobedience actions. Free Artists, a group of university students and teachers in the arts, artists, art historians, theoreticians, curators, and civilians, were the first ones to organize actions.12 The most outstanding moment in these early protest movement within the art field was, however, the so-called Ludwig Stairs. Under the group name of United for Contemporary Art (also including the Free Artists), various cultural workers occupied the main stairs inside of the Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art, Budapest in 2013, demanding institutional autonomy as well as transparency and professional dialogue in the highly questionable selection procedure the government generated around the institution’s then upcoming director.13

Ludwig Stairs occupation, United for Contemporary Art, Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art, Budapest, May 2013. Photo by Gabriella Csoszó/FreeDoc

While these events and processes resemble in some respects to earlier times in Hungary, the context and the mechanisms of power/repression are now very different. No initiations today are banned or subjected to be juried, i.e., ask for permission before opening to the public (as it was previously the case). Yet, the control of today’s regime is discernable through the heavy polarization of the local art scene along political lines, and often self-censorship, as well as a frequent sense and form of illegality when disputing and taking a stand against the dictates of the government. Furthermore, as various modes of self-organization seem to emerge as a way to work outside of the state infrastructure, it is also worth referring once again to Jelena Vesić’s essay on research into self-management, self-organization, and opposition to the state in Yugoslavia in the 1960s-‘70s, as she questions the actual political possibility of these notions in current neoliberal times.14 That is, as self-management in Yugoslavia traversed both the unofficial and the official spheres, today, as a highly valorized—also understood as critical—modus operandi of cultural workers in general, self-organization (also as self-exploitation and self-precarization) has likewise been co-opted by neoliberal capitalism as a form of production. How can one then oppose or be critical of the institutionalized establishment? Also, how to navigate in the Hungarian art scene today when any action is, or can politically be, heavily charged, begging a series of moral questions whenever an invitation or an opportunity arises? Also, how to function in an art scene that has only a tradition of state funding, and now private or civil funding, albeit not dominant, but currently seem to offer almost the only possibilities for critical art practices? These are some of the questions and dilemmas that underlie the context in which today’s critical/“progressive” initiations in Hungary are emerging.

The protest actions of 2012-2013 were important moments, as they pointed out the abuses of power in culture; nevertheless, they did not have much transformative effect in terms of society at large or in terms of results of negotiation attempts with the government. It was around 2014, when a tipping point can be seen in the very tactics of resistance: a transition from symbolic actions and a direct opposition to power to building something more sustainable and proactive, as a way forward, that manifests a kind of “positive resistance.”15 In this sense, the Action Day series initiated by the Budapest-based art organization tranzit.hu—where I work as a curator and that is supported by the private ERSTE Foundation—can be considered a transitional moment within the shift in the forms of resistance. Action Day was a series of discussion forums, taking place each month for a year, from April 2013 to April 2014. Through the involvement of activists, it was an attempt for facilitating, among others, community building and democratic forms of decision-making processes in (and beyond) the local art scene, with the hope of developing coalitions, alternates, efficient advocacy and actions that oppose and circumvent the state-directed reordering of art’s previous infrastructure. Even though participants of the forums were only active as long as the Action Day occasions were provided for as a program at tranzit.hu’s space, it was, at that moment, a quite radical form of trying to bring people together on a horizontal platform for a common cause.16

Action Day, Mayakovsky 102, the open office of tranzit.hu, Budapest, 2013. Photo by Zoltán Kerekes

Another project that can be considered to embody this positive form of resistance was the first edition of the OFF-Biennale Budapest in 2015. It was a grassroots initiative that emerged from the collaboration of many different actors of the contemporary art scene in Hungary, and also involved numerous international participants, mostly from the Central-East European region. From a local point of view, it was an outstanding project as, amidst the problematics of the art scene in Hungary, it was able to bring art professionals together—all working pro bono, out of enthusiasm— and it allowed for a new sense of a horizon and a network of solidarity to emerge. The one-month biennale functioned as an umbrella organization that united in one, decentralized framework and concerted communication more than 160 exhibitions and 200 events in 136 venues. In spite of the rigorous efforts of the many art practitioners involved to build up a non-traditional biennial, its organization unavoidably necessitated unresolved issues as well—for instance, the contradictions between democratic and hierarchal forms of modus operandi, the lack of a well-articulated program/theme, questions of sustainability, or the distribution of available funds.

As a political statement, the OFF-Biennale in 2015 was organized without any state funding and in venues that received no financial support from the state. Subsequently, most of the projects were realized with modest budgets or DIY ways, and the venues across Budapest included, besides non-state funded art spaces, for instance private apartments, a power plant, a former post office building, or an outdoor bar. The OFF-Biennale Budapest did not have any institutional support either; it did not have logistical-infrastructural backing, there was no institution behind it. The main financial sponsors were non-Hungarian civil funds (70%) and private individuals (30%) of the overall budget of HUF 40 000 000 (approximately USD 143 747), and some projects received additional funding from cultural institutions or in-kind sponsorship. As the majority of financial support came from civil funds, the biennale was also geared toward looking at “how art contributes to the development of civil society.”17 Overall—while the second 2107 iteration of the OFF-Biennale Budapest is under way—the first edition in 2015 was a major achievement: not so much because of the art projects it was able to realize, but because it was able to bring them together in way that sought out strategies of working together outside and beside the state-run art infrastructure. It is for this reason that Svetlana Boym’s theory of the Off-modern—of imagining “side alleys,” “lateral potentialities,” and “third ways”—served as the basis of naming the initiative.18

Horizontal Standing, exhibition at Népszínház utca 19. (a private apartment). Photo by The Orbital Strangers Project/OFF-Biennale Budapest Archive

The other pivotal project that can be regarded as a positive form of resistance, or as seeking a “third way,” is the so-called Living Memorial, ongoing since 2014. It started as a demonstration in March 2014, organized by a group of contemporary artists (again including also the Free Artists) as well as various individuals working in culture and humanities-related fields, against the plans of a monument the government ordered to commemorate the victims of the German occupation of Hungary in 1944 and the 70th anniversary of the Holocaust. The plan for the monument—which was eventually erected in July 2014—depicts Archangel Gabriel as innocent Hungary who is about to be attacked form above by an eagle symbolizing Nazi Germany. From the beginning, when the plans started surfacing, as well as during its construction, several groups, including what is now called the Living Memorial, started protesting against the monument as it reifies a falsifying history. It portrays Hungary as falling prey to Nazi Germany, and does not acknowledge the country’s contributing role in the Holocaust, and does not make any differences between victims and perpetrators in Hungary.19

The flash mob demonstration that the Living Memorial group organized aimed first to symbolically occupy and quasi consecrate the designated and otherwise meaningless site (beside an entrance to an underground parking lot at Liberty Square) of the then would-be monument by inviting people to place their objects of personal memories there (e.g. pebbles, candles, photos, etc.).20 The hope was that the authorities would not dare to remove the objects, and hence it would complicate the erection of the monument.21 Soon, another, more confrontational strategy also evolved that included placing a chair and the constant physical presence of a person sitting on it that would likewise make the completion of the statue harder.22 While several different, overlapping demonstration phases (and also other demonstrations) took place, a regular discussion circle also emerged on the Square: the “living cultivation of memory,” that is the so-called “Living Conversions” of the Living Memorial, of sharing personal memories and experiences.23 As it was pointed out, one of most important aspects of the Living Memorial was that the initiators did not assume the perspective of victimhood, and emphasized instead that Hungarian society at large needs to self-critically reflect on the Holocaust and on the past, not only the Jewish community.24

Living Conversation. In the background is the monument to the victims of the German occupation by Péter Párkányi Raab, August 15, 2014. Photo by Béla B. Molnár

The series and the logistics of the discussions/programs (providing sounds or chairs, building a winter pavilion, etc.) continue to be organized—relentlessly since 2014—and not only in Budapest, by a very active cross-generational group of diverse backgrounds, who also arrange for themselves self-educative, training workshops.25 Even though the Living Memorial group comprises and is able to address/mobilize only a small group of people, it has achieved a lot, not only in terms of the fact that the monument has not been inaugurated by the state since its installment. The Living Memorial was able to go beyond a simple opposition and protest against the state to focus instead on constructing a horizontal, dialogue-based and social sphere that can facilitate at meaningful discussion of opposing views. As Balázs Byron Horváth, a Living Memorial member underscored, the partner of these discussions is no longer the power, but the people themselves: one of their main objective is to teach and learn to organize civil life in society.26

In seems that projects such as the Living Memorial or the OFF-Biennale Budapest depend on the commitment, enthusiasm, and political awareness of individuals—“professional” and “civilian.” It is more than self-organization; in order to run these highly demanding projects, the people involved usually need to re-organize their lives to a degree that borders self-exploitation, and of course not everybody can do that. These positive forms of resistance, moreover, are not institutional critique: they go beyond “complaining”; their wish is not to return or reform previous infrastructures, rather, to imagine and build up something without it. It is not mere escapism either, as these initiations act as quasi public institutions and perform public functions, such as the support of critical art practices or revisiting the country’s troubled past.

—

Footnotes:

1. See more about it in the publication of the Vasarely Go Home project by artist Andreas Fogarasi: Franciska Zólyom ed. Andreas Fogarasi—Vasarely Go Home. Leipzig – Zürich: Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst – Spector Books – Museum Haus Konstruktiv, 2014.

2. See for instance, Edit Sasvári, “Cultural Repatriation as Political Strategy—Victor Vasarely and Kádár-Era Hungary.” Franciska Zólyom ed. Andreas Fogarasi—Vasarely Go Home. Leipzig – Zürich: Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst – Spector Books – Museum Haus Konstruktiv, 2014: 63–64.

3. See more about “unofficial art” and the “second public sphere” in general in Hungary, in, among others: Hans Knoll ed. Die zweite Öffentlichkeit. Kunst in Ungarn im 20. Jahrhundert. Dresden: Verlag der Kunst, 1999; János Sugár, “Schrödinger’s Cat in the Art World.” IRWIN ed. East Art Map. London: Afterall, 2006: 208-212; the website built around the conference Performing Art in the Second Public Sphere, http://www.2ndpublic.org/; Dóra Hegyi and Zsuzsa László, “How Art Becomes Public” László Zsuzsa ed. Parallel Chronologies, 2011, http://tranzit.org/exhibitionarchive/; as well as Barbara Dudás, “Polite Quietness—Current Trends in Eastern European Art History.” Mezosfera, Aug 11, 2016, http://mezosfera.org/polite-quietness/.

4. László Zsuzsa’s unpublished manuscript, 2014.

5. Jelena Vesić, “Post Research Notes. (Re)serach for the Ture Slef-Managed Art.” Paul O’Neill, Mick Wilon eds. Curating Research, London: Open Editions, Amsterdam: De Appel: 118–119.

6. Edit Sasvári, Ibid, 63, 67.

7. Sasvári, Ibid, 64–70.

8. The exhibition was produced for the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid in 2011, and it was shown at the Trafó Gallery in Budapest (2012), at the Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst, Leipzig (2014), as well as at the Museum Haus Konstruktiv, Zürich (2014).

9. For instance, curators and researchers László Zsuzsa or Beáta Hock.

10. See more on this, among others, Edit András, “Vigorous Flagging in the Heart of Europe: The Hungarian Homeland under the Right-Wing Regime.” e-flux Journal No. 57,09/2014, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/vigorous-flagging-in-the-heart-of-europe-the-hungarian-homeland-under-the-right-wing-regime/; József Mélyi, “Collective Time Travel Without a Future” Mezosfera, April 9, 2016, http://mezosfera.org/collective-time-travel-without-a-future/; Barnabás Bencsik, “The Steamroller Advances Relentlessly. The National Salon at the Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle, Budapest.” Mezosfera, April 10, 2016, http://mezosfera.org/the-steamroller-advances-relentlessly/.

11. See especially Bencsik, Ibid.

12. See on the website that collects information about various protests against the Hungarian Academy of Arts and current cultural politics in Hungary: https://nemma.noblogs.org/category/free-artists/.

13. See more about the Free Artists and the Ludwig Stairs in Edit András, Ibid, as well as Edit András, “Hungary in Focus: Conservative Politics and Its Impact on the Arts. A Forum.” Artmargins, September 17, 2013. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/interviews-sp-837925570/721-hungary-in-focus-forum.

14. Vesić, Ibid, 114–133.

15. My understanding of a positive form of resistance is also inspired, to a certain degree, by Vienna-based philosopher and art theorist Gerald Raunig’s concept of “instituent practice.” As Raunig put it (in relation to a third phase of institutional critique): “Figures of flight, of dropping out, of betrayal, of desertion, of exodus: these are the figures that several authors advance as poststructuralist, non-dialectical forms of resistance in refusal of cynical or conservative invocations of inescapability and hopelessness. With these kinds of concepts Gilles Deleuze, Paolo Virno and others attempt to propose new models of non-representationist politics that can be turned equally against Leninist concepts of revolution aimed at taking over the state and against radical anarchist positions imagining an absolute outside of institutions, as well as against concepts of transformation and transition in the sense of a successive homogenization in the direction of neo-liberal globalization. In terms of their new concept of resistance, the aim is to thwart a dialectical idea of power and resistance: a positive form of dropping out, a flight that is simultaneously an ‘instituent practice.’” Gerald Raunig, “Instituent Practices: Fleeing, Instituting, Transforming.” Gerald Rauning and Gene Ray eds. Art and Contemporary Critical Practice—Reinventing Institutional Critique. London: Mayflower Books, 2009: 8.

16. Another project that can be mentioned is Outer Space, organized by art critic József Mélyi and curators Eszer Kozma and Márton Pacsika. It was a series of exhibitions by Hungarian artists every week realized just outside of the Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle, in response and in protest to the fact that the ownership of Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle was handed over to the Hungarian Academy of Arts. See the project’s website: http://www.kivultagas.hu/

17. Press anouncment on e-flux: http://www.e-flux.com/announcements/off-biennale-budapest-2015/.

18. Svetlana Boym, Architecture of the Off-Modern. New York: Columbia University and Princeton Architectural Press, 2008: 4.

19. See also more on this: Edit András, Ibid (2014).

20. Dóra Hegyi, “Turning a Non-Place into a Place. An Interview with Members of the Living Memorial.” Dóra Hegyi, László Zsuzsa, Zsóka Leposa eds. War of Memories—A Guide to Hungarian Memory Politics. Budapest: tranzit.hu, 2015: 81.

21. Dóra Hegyi, Ibid, 81.

22. Dóra Hegyi, Ibid, 82.

23. Dóra Hegyi, Ibid, 90.

24. Anita Gócza, “Tétje lett ennek az egésznek” – Az Eleven Emlékmű két éve, Artportal, April 24, 2016, http://artportal.hu/magazin/kozugy/tetje-lett-ennek-az-egesznek-az-eleven-emlekmu-ket-eve

25. As one of the Living Memorial members, Balázs Byron Horváth recounted in an informal meeting with me in May 2016.

26. Anna Lénárd, Körbejárok – Beszélgetés a diszkusszív térről Horváth Balázs Byronnal. Balkon 3/2015: 16.