Posted on August 2, 2013

In 1973, Darryl Sapien and performance partner Michael A. Hinton appeared in the sunken basement of a demolished building on the corner of Third and Howard Streets in San Francisco. For an hour and half the two men, covered in war paint, wordlessly circled, shoved, wrestled, and fought with staffs while above them, two professional chess players called out the moves of their game, which were tracked by a youth on a large board visible to the audience above. Titled War Games, the performance highlighted the truth and equilibrium created by physical combat versus the intellectualized distance of a game, bringing to mind the gap between office-bound policy makers and those on whom their decisions have a direct effect.

For the opening of State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970 at The Bronx Museum of the Arts (June 23, 2013 – September 8, 2013), the artists’ sons, Joaquin Sapien and Jeffrey Hinton, re-staged War Games on the North Wing terrace of the museum. Performed nearly 40 years after the original, Son of War Games is as equally challenging and relevant as it was in the early 70’s.

From left to right: Darryl Sapien with Michael A. Hinton, Son of War Games, Bronx Museum of the Arts, 2013, credit: Frank Priscaro; War Games: Performance at Third and Howard Streets, San Francisco, 1973, credit Phillip Galgiani

HJ: Seeing the re-enactment of a historic performance by the children of the original performers was nostalgic, but also gave me a sinking feeling because I was watching the sons perform the same violence as their fathers. At the time of the original performance in 1973, War Games seemed to be a reflection on the fighting that was happening in Vietnam and violence on the streets in the United States. What was behind the idea of having Joaquin and Jeffrey re-enact the original performance? Does Son of War Games comment on how little the cultural and political reality has changed?

DS: It’s interesting to me that you found Son of War Games to be violent. From my perspective our sons’ interaction in the performance was an explosive collision of opposing forces, but controlled and intentionally non-violent. The series of actions they performed were identical to what Mike Hinton and I did forty years ago, and followed the same pattern of escalating tests of strength and endurance. It was designed to be more like an athletic contest than a pair of gladiators. Conversely, I saw it as an alternative to so much of the destructive violence occurring around the world. In fact conflict resolution was the underlying theme of the performance.

In 1973, when the original War Games was created I was deeply interested in the relationship between performance and ritual. Much of my previous work had focused on oppositional forces coming into conflict and how that energy could be deployed constructively, destructively, or go both ways at the same time. This led me to explore ritualized forms of conflict resolution in humans and animals. The early 1970’s was also the beginning of the information age when electronic communication was replacing older forms of human interaction. My feelings were that in this transition we had somehow lost our way, that we had lost contact with the mythic, with the archetypes, with much of what had over the millennia made us who we are. I perceived that the rituals that were once the cement that held societies together had either been utterly lost or replaced by mere games, like chess for example. War Games was a reflection of that time just as Son of War Games is a response to our present time.

Today we have not just one but two wars in progress and as we look around us, our society and the world appear to grow more deadly and destructive every year. Nowadays people seem to be ever more isolated and human interaction has become so diluted by our electronic devices that even the ability or desire to conduct a face-to-face conversation is becoming an option of last resort. I think these two trends are now more in a direct correlation than they were forty years ago.

HJ: Son of War Games both embodied and made me question the allure of violence and force, particularly in American culture. The performance also seemed to honor physical fighting over analytical games (ie. the chess match) happening concurrently. Can you talk a bit about this division?

DS: In both versions I sought to create a contrast between a game of conflict (chess), and a conflict ritual (one of my own invention), super-imposing one upon the other in real time and in the same space. My intent was to demonstrate how ritual can bring the participants together through cathartic physical actions whereas game separates participants by creating winners and losers, thus throwing individuals and societies out of balance. It was also meant to have a generational divergence. In 1973, Mike and I were the young generation looking for a different way to channel aggression into non-lethal forms while the chess players represented the older establishment. In 2013, our sons replaced us as the young seekers of a new way to mitigate hostility, while the fathers had been subsumed into the status quo.

There is also the political aspect of the older generation plotting and strategizing on their towers at a safe remove from the action, while the young men face off mano-a-mano.

HJ: What struck me about the performance was not only its intellectual associations but also its visceral nature. Son of War Games has been described as a re-enactment, a series of ritualized movements, and a mock fight. How much of the performance is prescribed motions and how much true aggression is allowed to come through?

DS: The first part of the ritual was for our sons to leave their 21st century identity behind and revert to a primal state. This was marked by the mutual application of opposite colored body paint and an ‘aggressive’ mask that each painted on the other’s face. The sequence of actions that followed was structured similarly to the chess game in that it was divided into three parts, opening, mid game, and endgame. The opening movements corresponded to threat/display behavior exhibited by certain higher mammals as described by Konrad Lorenz in his 1963 book “On Aggression”. These behaviors are employed to block aggression in other con-specifics, allowing the stronger to dominate and the weaker to retreat with no serious harm done to either. The mid game was the most active and energetic section. This part incorporated aspects of the formalized conflict rituals of the Yanomamo Indians of the Orinoco River Valley, such as chest pounding, along with the stick duel, which was of my own invention. Our sons were instructed to start out the stick duel like a game but to let it evolve into a contest of strength. At the first ‘check’ in the chess game they were instructed to break the stick and use the two pieces more like a weapon, not a club mind you, but more for leverage. Once they discarded the broken stick they engaged in a Greco-Roman style of grappling, each gripping only the other’s arms or shoulders. Once the chess game ended with black defeating white, the young men physically demonstrated their attainment of equilibrium by taking turns carrying each other one time around the central ring. Following that, the fathers descended from their towers to perform the lustration, the ritual bathing of their sons. This was meant to symbolize a cleansing of hostility, but also to show the subservience of the game players to the ritual combatants. It also served to visually bring them back the 21st century. This part was very moving for Mike and I, having washed our boys as children numerous times in this instance it was more like an homage to the effort they had expended in replacing us

There was no real aggression involved between Jeffrey and Joaquin; they’ve been friends since childhood just as their fathers remain friends today. There was a good deal competitive ardor, as one would expect between two young athletic males, but no animosity whatsoever. A central premise of the performance was that they could achieve a state of equilibrium through cathartic physical action while exhausting themselves in the process. At times they seemed truly possessed by the spirit of their fathers and eager to fully embrace what Mike and I had done a generation ago. Our sons had only heard about these performances in conversation, read about them, or seen them pictured. To them what Mike and I had done in the past was almost mythical. This was their opportunity to re-live the deeds of the mythical past, which is what rituals allow us to do, and they held nothing back. In this way the sequel surpassed the original because it became a true rite of passage. One in which fathers pass their history down to their sons and the bonds between them are reinforced.

Just for the record I want to also mention the significance of symbol that was painted on the floor. It is derived from the I-Ching and is called Broken Line Changing. It is a long black bar with a gap in the middle, and the gap is surrounded by a white ring. In the performance the chess towers, painted the opposite colors of red and green, were located at the far end of the bars. The ritual combatants (also red and green) proceeded from the towers along the black bar to meet inside the white ring. Similar to chess, where control of the center is paramount, the circle inside the white ring became the territory contested by the two combatants. One would hold the center while the challenger would circle around the ring looking for an opening and attempt to push his adversary out of the center to hold it himself. That is until the end, when the ring became the bridge that would unite the opposites.

From left to right: War Games: Performance at Third and Howard Streets, San Francisco, 1973, credit Phillip Galgiani; Darryl Sapien with Michael A. Hinton, Son of War Games, Bronx Museum of the Arts, 2013, credit: Frank Priscaro

War Games is on view in the ICI touring exhibition State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970 at the Bronx Museum of the Arts in New York from June 23, 2013 – September 8, 2013.

***Heather Jones is currently an Exhibitions Intern at ICI. She is completing her Masters in Curatorial Studies and Law at Stockholm University and is enrolled in the Architectural Theory and History Program at the Royal Academy of Art, Stockholm.

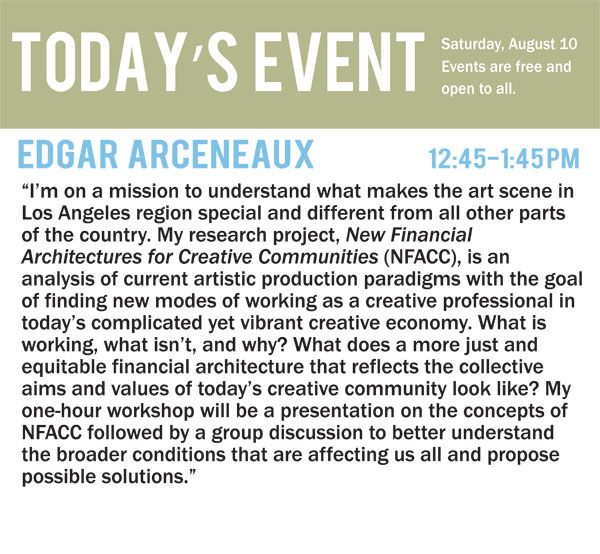

New Financial Architectures for Creative Communities (NFACC) Edgar Arceneaux August 10, 2013 12:45-1:45pm Armory Center for the Arts 145 North Raymond Avenue Pasadena (626) 792-5101 Summary of NFACC research goals My larger intentions with this research is continue formulating questions based on my interviews with artists across the United States for the CAA conference in Feb 2014. The workshop there will be set up along these lines: Individuals working in groups for a concentrated period of time analyzing a set of key questions. Group think towards common issues affecting the environment of the creative community today. The exact questions will be formulated through a year of research amongst creative communities across America. 1st Stage Research period Jan 2013-Feb 2014. Background For more then 15 years, I have maintained a vibrant and active art career, showing and lecturing internationally and at the same time Co-founded the organization Watts House Project, an innovative nonprofit arts organization that brought artists, architects and families together in a collaborative effort to transform the homes of their neighborhood surrounding the Watts Towers. In the process, I have come to understand the unique challenges of being an artist and art student today and have spent several years researching the economics of being an arts professional in America. What if there was a way for artists to foresee the best paths for their life, practice and career before they ever began art school or before they graduate? I believe there is a way to create a collection of terms and principles that the creative community could use to understand the implications of the broad spectrum of factors effecting their practice and career environment today. I believe this research can reveal a path to a more just and equitable financial architecture that reflects the collective aims and values of today creative community. In determining artists temperament and values in this ecosystem will enable us to operate fully aware of the systems affect on the content of our work. Its an expanded discussion, beyond that of market forces, backed by real examples of new financial architectures that must be an integral part of todays discourse on art and life.

New Financial Architectures for Creative Communities (NFACC) Edgar Arceneaux August 10, 2013 12:45-1:45pm Armory Center for the Arts 145 North Raymond Avenue Pasadena (626) 792-5101 Summary of NFACC research goals My larger intentions with this research is continue formulating questions based on my interviews with artists across the United States for the CAA conference in Feb 2014. The workshop there will be set up along these lines: Individuals working in groups for a concentrated period of time analyzing a set of key questions. Group think towards common issues affecting the environment of the creative community today. The exact questions will be formulated through a year of research amongst creative communities across America. 1st Stage Research period Jan 2013-Feb 2014. Background For more then 15 years, I have maintained a vibrant and active art career, showing and lecturing internationally and at the same time Co-founded the organization Watts House Project, an innovative nonprofit arts organization that brought artists, architects and families together in a collaborative effort to transform the homes of their neighborhood surrounding the Watts Towers. In the process, I have come to understand the unique challenges of being an artist and art student today and have spent several years researching the economics of being an arts professional in America. What if there was a way for artists to foresee the best paths for their life, practice and career before they ever began art school or before they graduate? I believe there is a way to create a collection of terms and principles that the creative community could use to understand the implications of the broad spectrum of factors effecting their practice and career environment today. I believe this research can reveal a path to a more just and equitable financial architecture that reflects the collective aims and values of today creative community. In determining artists temperament and values in this ecosystem will enable us to operate fully aware of the systems affect on the content of our work. Its an expanded discussion, beyond that of market forces, backed by real examples of new financial architectures that must be an integral part of todays discourse on art and life.