Posted on December 17, 2013

Cultivating the Human & Ecological Garden: A Conversation with Bonnie Ora Sherk, October 5, 2013  Bonnie Ora Sherk.

Bonnie Ora Sherk.

Bonnie Ora Sherk. Scene From PUBLIC LUNCH, February, 1971 – Lion House, San Francisco Zoo.

Bonnie Ora Sherk’s visionary work started in the very early 1970s in San Francisco with the creation of environments such as Portable Parks 1-111 (1970-71) on the elevated freeway, and performances such as Public Lunch (1971) at the San Francisco Zoo. Her early works exhibited in State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970 inserted a unique, environment-conscious, voice within the Conceptual Art movement growing in California at that time. They were the very first steps for Sherk’s explorations into human beings’ relationships with the natural world. A conceptual and transformational, public practice artist, Sherk is above all a human being who learned from nature and aims to share knowledge about ecology, art, and systems, through larger-scope community projects such as A Living Library. In this conversation, Sherk reflected on her earliest works and her most recent projects, giving an insight on her trajectory as an artist, an educator, and a cultivator – literally and metaphorically – through a few decades’ time.

Pierre-François Galpin: Regarding the exhibition State of Mind: New California Art circa 1970, could you speak about the California art scene at that time? When did you arrive in San Francisco?

Bonnie Ora Sherk: I arrived in San Francisco in the very late 1960s. I had just graduated from Douglass College, Rutgers University, in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and it was time for a new adventure, to do something different! I had never been to California before, but I was aware of the Summer of Love (1967), so it was of interest, of course. When I first came, it took me about a year to feel comfortable, as I am very sensitive to the environment, landscape, and vegetation; everything was different from the East Coast. In California, the landscape seemed very dry, and not very green. I was born in Massachusetts, and I moved around with my family in Maryland and Virginia, until we settled in New Jersey when I was in second grade. I was living very close to New York City, experiencing the metropolitan region and city life. The town where I lived, Montclair, New Jersey, had fabulous old, deciduous trees; it was very leafy, green, and beautiful.

PFG: What do you think was specific to the California art community compared to other art scenes, especially New York? Were you aware of the art scene in San Francisco?

BOS: When I first arrived in San Francisco, I knew very few people, and initially none from the art community. But, I became a graduate student in Fine Arts at San Francisco State University, and, in 1970, I began to meet serious, professional artists, when I created my first public project, Portable Parks I-III, which transformed “dead spaces” into ephemeral, bucolic, green places. Portable Parks brought trees, live animals, and other related elements to an elevated freeway, concrete islands next to a freeway off-ramp, and a whole street that was closed off, creating temporary parks, each increasingly more participatory.

Around that same time I met Tom Marioni, Terry Fox, and other artists involved with Marioni’s Museum of Conceptual Art in San Francisco. I really resonated with their work. I felt at home. It was a very exciting period for art, and for me. It felt open and freeing – very innovative, moving, beautiful, and at the same time – challenging.

After Portable Parks, I began exploring the nature of what a performance could be, including its environment and context – either found or created, and who the audience could be. In Portable Parks, I used live animals as elements in the work, and considered them to be performers, as was I. The places for the performances were also important, and functioned as integral to the works. I considered these pieces to be environmental performance sculptures.

At that time, and still now, my work has to do with equality between humans, and other species. In later works, like Public Lunch, Living In The Forest (1973), and The Raw Egg Animal Theater at The Farm, I created juxtapositions of humans and other animals in performances and installations, to call attention to issues of racism, sexism, and child abuse. I was, and still am, with A Living Library, working on a more planetary, ecological understanding of who, and where, we are in the universe and on the planet, in relation to other species and phenomena.

During that early period, I was not thinking so much about my career and exhibitions; that was not the main point or issue. I was exploring different ways to express ideas and feelings, and communicate what I was experiencing and learning. The art world did not appear to be interested, supportive, or understanding of what I was doing then. I had to create my own venues and opportunities, although a few of the artists at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, showed some interest.

PFG: Could you talk about the relationship between conceptual art and ecology in your own practice, in Public Lunch, for instance?

BOS: During Public Lunch at the San Francisco Zoo, I had a human meal in the Lion House, adjacent to cages in which lions and tigers were having their meals of raw meat. At this time, I had been thinking a lot about analogies in diverse forms, and juxtapositions of imagery. I thought it would be interesting to have lunch at the same time as the lions and tigers, at the public feeding time of 2 pm, when people come to the Zoo to see the animals being fed. I was one of the animals being fed. In the cage with me was another cage with a rat inside – a cage, within a cage, within a cage. Who is in the cage?

The idea for Public Lunch was initially inspired by room service breakfast I ordered when I stayed at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in Manhattan, as a guest of Mademoiselle Magazine, which had named me as a Woman of The Year (1970), for my work with Portable Parks. For breakfast, I ordered a very simple meal of poached eggs on toast and black coffee. A very elaborate table was wheeled into my room, with a white tablecloth and many covered dishes. After breakfast, I walked to the Central Park Zoo and visited the Lion House, and the total vision for the piece crystallized. When I returned to San Francisco, I approached the Zoo staff and they agreed to let me do this performance.

Public Lunch began when I was let into my cage from the outdoor cage in a similar way as the other animals. During the course of the performance, I paced, as did the tigers next to me, and I ate a human meal, served in a similar way as the other animals, through the bars in a small cage door. I ate a grilled steak, salad, bread and butter, and drank a cup of coffee, while the tigers and lions ate raw meat. After I ate, I paced some more, and then climbed up a ladder to the platform in my cage. I spent some time writing, (another human activity), and then lay down and looked up at the skylight above, seeing birds flying overhead. The tiger in the adjacent cage, who was also on his platform eating, turned around, got up on his haunches, peered over, looking at me. I could tell that he was perceiving me, and I thought,

“ He sees me. Is he thinking and feeling, too? What is he thinking?”

That awareness led me to begin working with different species of animals, studying their behavior, interactions, and communications, and closely observing them. I learned about ecology and natural systems from them; they were my teachers. And, I also learned more about art from them. The rat from Public Lunch, was the first animal I worked with in this way. Other species were later introduced into my studio-laboratory environment.

In the early 1970s, the field of ethology was very new, and there was very little written literature available. One of the few authors I could find, who had written on animal behavior was the Austrian zoologist, Konrad Lorenz, and I read much of his work. I then also began to read all I could about organic gardening, ecology, and natural systems.

PFG: Your performances took place primarily in outdoor public spaces. They also can be read as interventions, interruptions of everyday life for viewers, such as the Zoo visitors in Public Lunch, or people in the streets during the Sitting Still series. In what ways is it different to perform in public spaces than to perform in a traditional white cube?

BOS: I was contrasting and juxtaposing elements, creating a sense of surprise, in order to awaken the audience, to facilitate their “seeing”. I did both outdoor and indoor performances. I created Sitting Still 1 (1970) soon after Portable Parks. I found an area of water filled with garbage near where the 101 freeway interchange was being built. In the center of the space was a large, overstuffed armchair. I immediately saw myself seated in the chair, surrounded by the floating tires, tricycle, and other garbage. I went home, put on an evening gown, called my friend Robert Campbell, and asked him to photograph me and the scene in a particular way. I came back to the site, waded into the water, and I sat in the chair, facing the “audience” – the people sitting in the slow-moving cars, due to the freeway construction.

It was a very direct intervention, demonstrating how very simply, a seated human figure could transform the environment. I took this idea and explored it further, and the Sitting Still Series evolved. I brought an armchair with me to diverse neighborhoods and places around San Francisco, and sat in various environments: at 20th and Mission Street, in the Mission; at Church and Market, in the Lower Castro; in the Financial District at California and Montgomery; on the Bank of America Plaza – the original Occupy; and on the Golden Gate Bridge. I also sat in various indoor and outdoor cages at the San Francisco Zoo. The juxtapositions seemed very surreal at the time, because my simple gesture appeared to be unusual, even though it was so ordinary. The Sitting Still Series culminated in Public Lunch.

I also created some indoor pieces, like Pig Sonata (1971), performed at the Museum of Conceptual Art. For that piece, I was dressed in an elegant, formal, long black gown. In front of the audience, I created a large pile of earth in the gallery space, by emptying numerous brown bags, covered the mound in raw vegetables, and made a trail of food, leading to a large wooden crate. I then opened the crate, out of which came a large pig, who followed the trail of food to the soil mound with the greater amount of food, climbed onto it, and continued eating. The piece lasted until all the food was eaten.

Another more elaborate, indoor, environmental performance sculpture, was Living In The Forest: Demonstrations of Atkin Logic, Balance, Compromise, Devotion, Etc. Created in 1973 at the De Saisset Art Museum in Santa Clara, CA, Living In The Forest was a metaphor for life in all of its aspects, including birth, death, struggles for survival, compromise, living our daily lives, etc. It was a very rich, complex, series of elements and actions that the public could enter. To describe briefly: in one of the galleries, I created a living environment with plants and animals set up on the north, south, east, west axis corresponding to the larger world. For six weeks, the museum was transformed: facing southwest, I planted six trees in a large, long box. Each was in a different state of life; the trees that looked dead were dormant; the tree that looked the most alive had no roots. It was a demonstration of illusion and reality. Each tree was surrounded by a wire mesh enclosure that I would cut and open to the animals, each week, to become part of their environment. In addition to me, the participating animals included, Pigme, a pig, hens and a rooster, rabbits including The Lady Doe, her mate, Buck, and their offspring, Mein Herr and Your Herress, two Ring-necked doves, and Guru Rat, the same rat who performed with me in Public Lunch. In the center of the environment was the center of the universe, facing east. Supported by nearby trees was a platform, which was my space, where I could lie down and rest, named, and written on its side, “layer of compromise.” All of the animals were performers: I performed human activities, like writing on the walls, including an alphabet, which described the diverse meanings and metaphors of the piece, as suggested in the title. The other species performed according to their habits: The rooster crowed and the hens laid eggs, making loud exclamations when laying their eggs and when the rooster mounted them. The doves made a nest in one of the trees and took turns sitting on their eggs. The buck chased his son to the kill, performing demonstrations of territorial struggles. The Lady Doe found the one safe place in the environment, under the tree that had no roots, in which to dig her warren and deliver her babies, which she fiercely protected. When I realized this after the fourth week of the exhibition, I did a Change of Mind Piece, and stopped cutting the wire mesh around the trees, so the warren would be protected. And, as another result, the last tree came into bloom. The Guru Rat died of old age, and so on.

During the course of the exhibition, many school groups came to visit, and entered the environment. After that experience, I was determined to create a healthier, indoor/outdoor environment for animals in a public space, where people could learn about natural systems, and appreciate the native intelligences of different species. The Raw Egg Animal Theatre (TREAT) at The Farm, my next major work, evolved directly from Living In The Forest.

PFG: I would like to understand more, how from these performances, or, how you call them, “environmental performance sculptures,” you then began, The Farm.

BOS: It’s actually quite fascinating and powerful. When I performed Sitting Still 1, unbeknownst to me at the time, I was literally facing my future: the site that would become The Farm, and the northern frame of the Islais Creek Watershed in San Fransicso, that I am still deeply involved with today.

Regarding The Farm: in 1974 the Borden’s Dairy was razed and became an open space covered in concrete. There were many other adjacent land fragments, next to and including the freeway interchange, which were owned by disparate entities. The largest parcel of open space, the old Dairy site, was acquired by Knudsen Dairy. Adjacent to it was a privately owned, one acre open space, and then just due south was a cluster of buildings, also privately owned. Alongside the buildings was a strip of land, owned and managed by the State of California, and in the center of the freeway was land owned and managed by the City of San Francisco. It was a diverse series of real estate entities to deal with. All of these open spaces were juxtaposed with the freeway interchange, a technological form of nature, creating an interesting diptych between the mechanized and non-mechanized forms of nature. The site also was at the convergence of three hidden creeks, and in the confluence of four low-income, high-need neighborhoods, that had been severed by the building of the freeway interchange. The idea was to bring everything together and make things whole.

In addition to wanting to develop a place where people could experience live animals, I saw this land configuration as a way to bring people from these diverse communities together, as well as plants and animals. It was a very important opportunity that eventually resulted in a new city park that was originally activated and inspired by The Farm. At the time, I also felt the need to bring different kinds of artists together: diverse kinds of visual artists – painters, sculptors, printmakers, photographers, videographers – with performing artists – dancers, musicians, actors, acrobats, clowns, jugglers. During this time, there was a lot of prejudice and chauvinism among artists. Around this time, I met a musician who was looking for rehearsal spaces, and I immediately saw that this open land and buildings could be transformed with indoor and outdoor spaces into a theater, farm, gardens, learning zones, etc. Crossroads Community (The Farm), as I named it, was born!

Many different kinds of people came to The Farm, including many school groups. I think they appreciated the surreal setting with the many Freeway Gardens, The Raw Egg Animal Theatre, the performances, and the community meetings and presentations. I stayed with The Farm until the end of 1980, as I felt I had accomplished as much as I could.

PFG: A Living Library, is a natural evolution of your previous projects, or “life frames”, as you call them. It is about bringing awareness of ecological systems through art into a public place; it goes back to your performances and installations in the 1970s. Could you talk about A Living Library and its different forms?

BOS: In 1981, I found myself in New York City, and began spending time in Bryant Park, in the heart of the City, at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue, adjacent to the main research branch of the New York Public Library, not too far from the United Nations. This site inspired A Living Library. At that time Bryant Park was known as “Needle Park”, because that’s where all the drug dealers went to sell drugs. There were no other really “good” uses of the Park; the dealers simply filled the void. I spent time in this seedy, yet elegant Park, feeling the place and its energy. Suddenly, I had an epiphany and saw how to make it come alive for other uses. I would bring the inside of the Library outside and create gardens of knowledge, based on the Dewey Decimal System, which fit perfectly around the peripheral gardens of the Park. In each garden of knowledge would be plants that related to the subject, visual and performed artworks, programs of lectures, demonstrations, and research institutes, and digital technologies that would bring out information from the Library and also enable this environment to be interconnected with others in diverse communities around the world.

It could become The Living Library! But, then, I realized that might be insulting to its neighbor, the New York Public Library, so I changed the name to A Living Library, meaning another library. Then I realized, the initials spelled A.L.L., the embodiment of what I was hoping to achieve. I was thrilled!

I worked very diligently to realize A Living Library in Bryant Park, but, ultimately this did not happen, although many of my ideas were later incorporated into its eventual renewal, such as the interactive community programs, and the extremely successful and lucrative, international fashion shows during Fashion Week.

It took me some time to figure out how to clearly articulate what I was envisioning, because it was so complex, layered, and new to the vernacular of landscape architecture. I knew that I was working on something really exciting and relevant, so, I continued to develop the idea of a programmed landscape, which at the time, was very innovative and unusual. I began to study landscapes from around the world and found many precedents for what I was envisioning, from Asia – in Chinese, Japanese, and Indian Gardens – and from the West – in Medieval Gardens, 17th Century French formal gardens, Renaissance Gardens, and others.

I was inspired to actualize this work, so, I went back to school to become a landscape architect, as a way to hone my skills, and be taken more seriously by the establishment that controlled public spaces. I was interested in creating and transforming public places as interactive parks and gardens, integrated with local community programs, interdisciplinary, hands-on curricula, that provided opportunities for learning about natural systems, ecology, local resources, and multicultural diversity.

I made many place-based, Living Library plans for diverse sites and situations over the years, including, a 1995-96, San Francisco Civic Center Living Library Conceptual Master Plan, for another underused, derelict, and neglected Beaux Arts Park. The idea here, was to create a 21st Century heart of the city, by outwardly reflecting and showcasing what is occurring in the surrounding civic buildings in the Plaza, and who San Franciscans are, as an international, multicultural community. The Mayor at the time, Willie Brown, was not interested in this opportunity, although many others were, including many other elected officials, the Board of Education, Sister City groups and consulates, funders, and many others.

Just after this, I found myself at James Denman Middle School, where the principal had heard about A Living Library, and asked me to begin one there. That began the OMI/Excelsior Living Library & Think Park that linked a high school, middle school, and child development center on a contiguous nine acre site. I developed a master plan with the three-school community, and as a pilot, we created a Garden between the Middle School and CDC, and along the streets, digging up concrete to create a California Native Learning Zone Streetscape Transformation & ArtWalk. Later, other asphalt areas were dug up and transformed into diverse learning zones. The processes involved students and the local community in research, planning, design, implementation, use, maintenance, management, and communications of their OMI/Excelsior Branch Living Library & Think Park. It is still underway today.

A Living Library is a planetary genre, developing locally and globally. Each resulting Branch Living Library & Think Park incorporates local resources – human, ecological, economic, historic, technological, aesthetic – seen through the lens of time – past, present, future. In addition to linking local resources and communities, a goal is to interconnect Branch Living Library & Think Parks in diverse communities, through sculptural, green-powered digital gateways, so we can share diversities and commonalities of cultures and ecologies, near and far.

A Living Library is a life work, and a life’s work. In addition to transforming sterile, barren environments, we are improving education, contributing to the public realm, training and creating new green jobs, and performing community and economic development in locales where A.L.L. is established.

For more information, see A Living Library blog and website:

http://www.alivinglibrary.org/blog

http://www.alivinglibrary.org

* Pierre-François Galpin is a CCA Curatorial Studies MA Candidate and former ICI Exhibitions Intern

Bonnie Ora Sherk.

Bonnie Ora Sherk.

Entitled Fresh Performance: Contemporary Performance Art in New York City and the Caribbean, damali’s documentary is less about the specific performance works of the twelve artists that she interviewed but is instead more about the artists’ conceptions of performance art as a practice within the context of their work. In the first few minutes of the film we are introduced to differing considerations of what performance art is from the twelve artists, which for the viewer emphasizes the interpretive nature of performance art and its malleability as an art form. damali has paired the video interviews with still images of the live performances of each artist, which creates an intriguing juxtaposition of interview as performance, and performance as documentary.

Entitled Fresh Performance: Contemporary Performance Art in New York City and the Caribbean, damali’s documentary is less about the specific performance works of the twelve artists that she interviewed but is instead more about the artists’ conceptions of performance art as a practice within the context of their work. In the first few minutes of the film we are introduced to differing considerations of what performance art is from the twelve artists, which for the viewer emphasizes the interpretive nature of performance art and its malleability as an art form. damali has paired the video interviews with still images of the live performances of each artist, which creates an intriguing juxtaposition of interview as performance, and performance as documentary. The role of documentation in performance art is fairly ambiguous given that some artists have denied any documentation of their work (claiming that it shall not exist outside of the moment of its performance) and others rely on documentation to preserve their performance (normally for exhibition purposes). damali complicates this ambiguity even further by turning an act of documentation into a performance itself. For her, the documentary is as much a performance as the works that we see in the still images shown in the documentary. The result of this is that as viewers, we are experiencing the binary of watching a live performance art piece by one artist in which she interviews other artists about their practice and calls on them to recollect past performances. This play with documentation and temporality demonstrates that performance can be something direct but not necessarily something that is easily understood by the public.

The role of documentation in performance art is fairly ambiguous given that some artists have denied any documentation of their work (claiming that it shall not exist outside of the moment of its performance) and others rely on documentation to preserve their performance (normally for exhibition purposes). damali complicates this ambiguity even further by turning an act of documentation into a performance itself. For her, the documentary is as much a performance as the works that we see in the still images shown in the documentary. The result of this is that as viewers, we are experiencing the binary of watching a live performance art piece by one artist in which she interviews other artists about their practice and calls on them to recollect past performances. This play with documentation and temporality demonstrates that performance can be something direct but not necessarily something that is easily understood by the public. Despite the drastic differences amongst the various pieces discussed, several common threads surfaced throughout the interviews, such as the importance of the audience, the role of spontaneity and interaction, and an appreciation of the unpredictable nature of performance art. This overarching notion of the role of the public sparks many questions for me. Can we have cross-cultural notions of performance art? Does a Barbadian audience approach damali’s work differently than a New York audience? Given that all of the artists interviewed deal with issues of identity, how do their audiences inform and interpret these issues based on their geographical location? Of course these questions remain unanswered, but I believe that is exactly what damali is trying to show us.

Despite the drastic differences amongst the various pieces discussed, several common threads surfaced throughout the interviews, such as the importance of the audience, the role of spontaneity and interaction, and an appreciation of the unpredictable nature of performance art. This overarching notion of the role of the public sparks many questions for me. Can we have cross-cultural notions of performance art? Does a Barbadian audience approach damali’s work differently than a New York audience? Given that all of the artists interviewed deal with issues of identity, how do their audiences inform and interpret these issues based on their geographical location? Of course these questions remain unanswered, but I believe that is exactly what damali is trying to show us. Ultimately, damali is offering these artists a chance to both explore and explain what performance art means to them, while forcing her audience to ask themselves the same questions. Her exploration of the medium through the words of these twelve artists initiates a much-needed discussion of the role that performance art has to play in the Caribbean, and simultaneously links it to performance art in New York. The connections that damali is making between the Caribbean and New York through the dialogue that she maintains with the twelve artists are unique, given that performance art is practiced by such a small number of Caribbean artists. Perhaps the most telling sign of this was not only in the words of the Caribbean artists on the screen, but even more so in the responses given by the audience members attending Fresh Event XIII. After the screening damali was met with questions from young art students who had either never heard of performance art or had never considered it in great detail, but who will now hopefully perpetuate this important discussion.

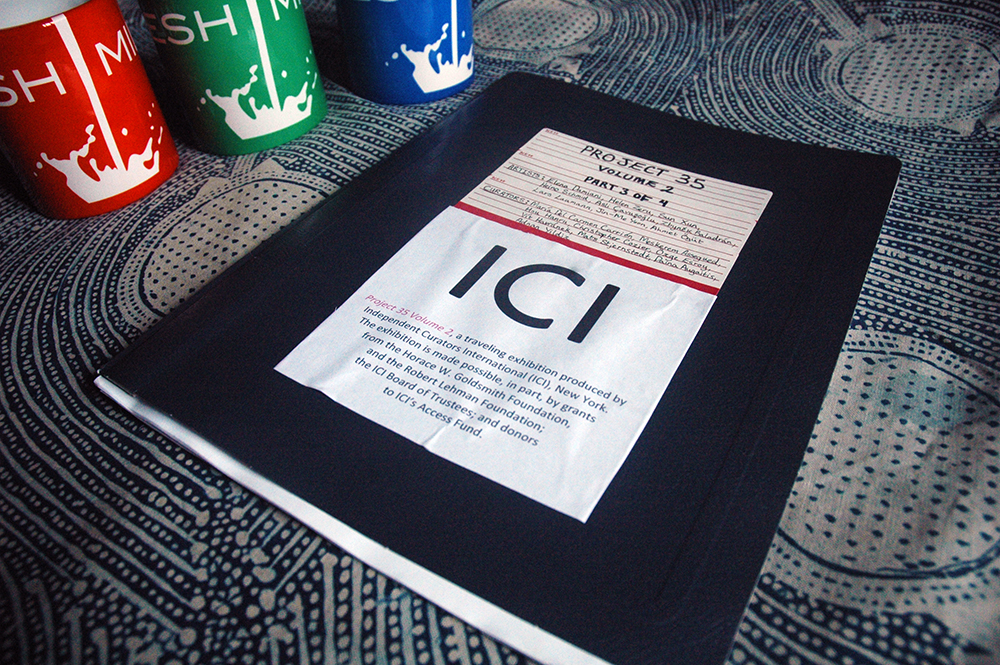

Ultimately, damali is offering these artists a chance to both explore and explain what performance art means to them, while forcing her audience to ask themselves the same questions. Her exploration of the medium through the words of these twelve artists initiates a much-needed discussion of the role that performance art has to play in the Caribbean, and simultaneously links it to performance art in New York. The connections that damali is making between the Caribbean and New York through the dialogue that she maintains with the twelve artists are unique, given that performance art is practiced by such a small number of Caribbean artists. Perhaps the most telling sign of this was not only in the words of the Caribbean artists on the screen, but even more so in the responses given by the audience members attending Fresh Event XIII. After the screening damali was met with questions from young art students who had either never heard of performance art or had never considered it in great detail, but who will now hopefully perpetuate this important discussion. In addition to damalis documentary, there was also a screening of Project 35: Volume 2, which is a travelling exhibition produced by Independent Curators International (ICI) and included a piece by Bahamian artist Heino Schmid, selected by Trinidadian artist and curator Christopher Cozier. Subsequently the director of Fresh Milk, Annalee Davis, took to the floor to present to the audience a series of other projects that had been in the works at Fresh Milk over the past few months. The first of these was the Fresh Milk Artboard, which was erected at the bottom of the road leading to the Fresh Milk site as a new public gallery from which the work of contemporary artists will be showcased. The first work to be displayed on the Artboard was designed by Barbadian artist Evan Avery, who had also previously designed a graphic work to be installed in the front window of Casa Tomadas A Casa Recebe in Brazil, which exhibits the work of both local and international artists. The relationship between Fresh Milk and Casa Tomada is just one example of the cross-cultural exchange that Fresh Milk is encouraging and that we are beginning to see more and more in the arts of the region and further afield. In light of this, Annalee also presented the Fresh Milk Virtual Map of Caribbean Art Spaces. This resource is an online map indicating the existing art spaces across the region, which also includes links to the websites of these spaces. Working to circulate information regarding arts in the Caribbean, this map not only offers a regional view of how these spaces have manifested themselves across the Caribbean but will hopefully help to facilitate greater connectedness between these institutions. Finally, Annalee directed the audiences attention to the addition of new publications to the Colleen Lewis Reading Room, located on the Fresh Milk site.

In addition to damalis documentary, there was also a screening of Project 35: Volume 2, which is a travelling exhibition produced by Independent Curators International (ICI) and included a piece by Bahamian artist Heino Schmid, selected by Trinidadian artist and curator Christopher Cozier. Subsequently the director of Fresh Milk, Annalee Davis, took to the floor to present to the audience a series of other projects that had been in the works at Fresh Milk over the past few months. The first of these was the Fresh Milk Artboard, which was erected at the bottom of the road leading to the Fresh Milk site as a new public gallery from which the work of contemporary artists will be showcased. The first work to be displayed on the Artboard was designed by Barbadian artist Evan Avery, who had also previously designed a graphic work to be installed in the front window of Casa Tomadas A Casa Recebe in Brazil, which exhibits the work of both local and international artists. The relationship between Fresh Milk and Casa Tomada is just one example of the cross-cultural exchange that Fresh Milk is encouraging and that we are beginning to see more and more in the arts of the region and further afield. In light of this, Annalee also presented the Fresh Milk Virtual Map of Caribbean Art Spaces. This resource is an online map indicating the existing art spaces across the region, which also includes links to the websites of these spaces. Working to circulate information regarding arts in the Caribbean, this map not only offers a regional view of how these spaces have manifested themselves across the Caribbean but will hopefully help to facilitate greater connectedness between these institutions. Finally, Annalee directed the audiences attention to the addition of new publications to the Colleen Lewis Reading Room, located on the Fresh Milk site.  Fresh Milk XIII, which marked the platforms final public event for 2013, fittingly brought together several of the elements integral to Fresh Milks mission; regional and international collaboration, experiment and exchange, knowledge of the contemporary arts, and increased visibility of Caribbean art all came into play. Moving forward, it is imperative to find the best way to activate these resources that Fresh Milk has made available, and continue to nurture the relationships built with artists such as damali and institutions such as ICI. In this way Fresh Milk will continue to evolve not only as an organization, but as an entity facilitating change by inspiring new ways of thinking, reaching new audiences and stimulating the publics sensibility as we move towards intellectual and creative growth.

Fresh Milk XIII, which marked the platforms final public event for 2013, fittingly brought together several of the elements integral to Fresh Milks mission; regional and international collaboration, experiment and exchange, knowledge of the contemporary arts, and increased visibility of Caribbean art all came into play. Moving forward, it is imperative to find the best way to activate these resources that Fresh Milk has made available, and continue to nurture the relationships built with artists such as damali and institutions such as ICI. In this way Fresh Milk will continue to evolve not only as an organization, but as an entity facilitating change by inspiring new ways of thinking, reaching new audiences and stimulating the publics sensibility as we move towards intellectual and creative growth.  About Jessica Taylor: Jessica Taylor recently graduated from McGill University with an undergraduate degree in Art History and Philosophy and hopes to begin a graduate degree in Curatorial Studies in 2014. Her focus is contemporary Caribbean art.

About Jessica Taylor: Jessica Taylor recently graduated from McGill University with an undergraduate degree in Art History and Philosophy and hopes to begin a graduate degree in Curatorial Studies in 2014. Her focus is contemporary Caribbean art.  Martha Wilson: Exhibition Windows at NYU

Martha Wilson: Exhibition Windows at NYU

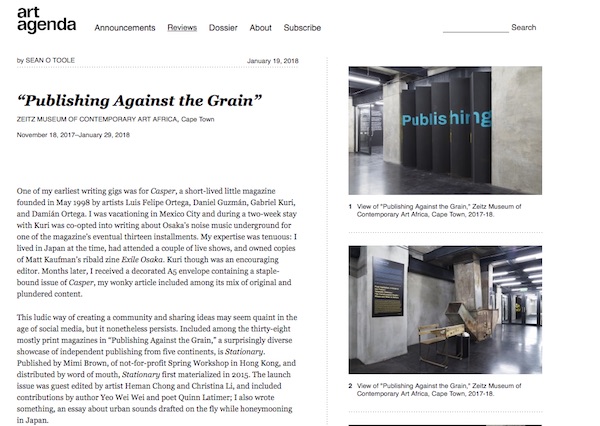

Ilze Wolff (Pumflet Editor) at the Publishing Against the Grain opening, Zeitz MOCAA, 2017. Photo courtesy of ICI and Zeitz MOCAA. ICI: While the museum will present an extensive collection of works from throughout the continent and abroad, how do you see international engagement through traveling exhibitions fitting into Zeitz MOCAAs future? Sven Christian (SC): International engagement through traveling exhibitions will play an important role in the realization of Zeitz MOCAAs mission to develop intercultural understanding. Another complimentary function of traveling exhibitions will be to help locate the collection within a global context, and to challenge the misconception that art from Africa is a homogenous, isolated entity. On a local level, traveling exhibitions are a great way for us to engage with parallel histories. They provide exposure to new material and offer alternate tools and approaches to problems similar to our own. Publishing Against the Grain was our first collaboration with Independent Curators International (ICI). It was also the first traveling exhibition to be held at Zeitz MOCAA. The importance of hosting traveling exhibitions like this was made evident through many of the interactions that we had with visitors over the course of the exhibition, and through the supplementary panel discussions that were held. Our attendance increased with each iteration and the large number of people who returned indicate that there is a demand for the types of discussions that the exhibition prompted. ICI: Publishing Against the Grain made its debut at the museum this fall. What about this exhibition did you and museum visitors find particularly interesting, and how can such publishing projects which disseminate alternative, progressive, and autonomous positions appeal to a Cape Town audience right now? SC: It was the scope of the exhibition and the prospect of new material that was most appealing. There were over twenty projects included in this exhibition, drawn from regions as far reaching as Peru, Uganda, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Hong Kong, and the United States. All of the core initiatives are still active today while some of their nominations were produced during the 70s, and now exist as records. Because each of these initiatives are specific to a particular time and place, we tend to think about them as isolated entities. However, having them all together in one space revealed many of their similarities. It also provided a great opportunity for us to understand the various contexts that gave birth to them, and to reinterpret these concerns and methodologies. Over the past few years, the need for alternate spaces within South Africa has become increasingly apparent. This is not to say that such initiatives are by any means newSouth Africa has a rich history of independent publishingbut that whenever a given framework is no longer able to support the needs of the voices it lays claim to, it is the unknown potential of new material that has the capacity to offer unseen solutions. In addition, the exhibition highlighted the amount of international visitors to the museum especially during the December-January period, when there is an influx of tourists in Cape Town. Many of these visitors were delighted to find publications on exhibition from their own country that they did not know existed. Being able to discover something in South Africa that was produced in your own backyard is something that I think will be important for the museum going forward, as traveling exhibitions like Publishing Against the Grain help make visible the various undercurrents that both bind and separate us. ICI: We conceived of this exhibition, as part of the curatorial framework, to generate new content and propositions at every venue. We wanted discourse to adapt to a site and the project’s changing contexts. Similarly, this exhibition continues to grow and accumulate as it travels, when new publications are added at every museum. We wanted to continue to open up a platform for discourse by inviting the curators we work with to add materials they have found influential to their particular scene. Can you explain how you framed and expanded Publishing Against the Grain for a Cape Town context? SC: The two publications I invited to take part in the traveling exhibition were Adjective and Pumflet. Adjective is an arts publication that bridges the divide between critical essay writing, poetry, and the visual arts in South Africa. Pumflet, on the other hand, is a site-specific, collaborative periodical that began as a conversation between architect Ilze Wolff and artist Kemang wa-Lehulere. As a collective they explore the relationship between the built environment and the social imagination. Like many of the initial projects drawn from ICIs international network, these publications were produced through collaborative, DIY means. They function as platforms for further research and the cross-pollination of ideas. This was something that we wanted to develop further, and became the framework for a series of supplementary panel discussions titled Alternate Voices. Alternate Voices provided visitors with a first-hand account into the origins, thought processes, and concerns behind some of the publications on exhibition. It also presented a platform for these ideas to be expanded upon within the context of artistic and critical production in South Africa. For each iteration we invited one of the core publications on exhibition to speak with one or two local practitioners. Due to their relevanceand because their concerns were common to many of the publications on exhibitionthe four that we approached were Our Literal Speed (United States), Pages (Iran and the Netherlands), Makzhin (Lebanon and the United States), and Exhausted Geographies (Pakistan). The thematic focus of each panel was drawn directly from the ideas expressed in each of these publications. For the first iteration local artists Mitchell Messina (Adjective) and Emily Robertson spoke with Our Literal Speed founders Matthew Jesse Jackson and John Spelman about their own practices and the relationship between art, capital, and popular culture. For the second, Tazneem Wentzel (Burning Museum) and Ashley Walters spoke with Babak Affrassiabi (Pages) about whether or not art could rely on the archive as a historical premise. Inspired by Makhzins open call for their upcoming issue Dictationship, the third iteration with Palesa Motsumi (Sematsatsa Library), Nick Mulgrew (Prufrock and uHlanga), and Mirene Arsanios (Makhzin) focused on the material conditions that dictate the way we write ourselves into the world. The fourth iteration was a conversation between Shahana Rajani and Zahra Malkani (Exhausted Geographies), who spoke with Ilze Wolff (Pumflet) about the long-lasting effect of the colonial blueprint in the development of former British colonies, Karachi and Cape Town. I hope our discussions will be useful to future audiences as it offers fresh insight into the motivations that underpin some of the projects in the exhibition. I think our conversations also provided an interesting perspective into how these projects were interpreted by Cape Town audiences, and will give some background into the two publications invited by Zeitz MOCAA Adjective and Pumflet which I’m very excited to see grow wings and continue on the tour.

Ilze Wolff (Pumflet Editor) at the Publishing Against the Grain opening, Zeitz MOCAA, 2017. Photo courtesy of ICI and Zeitz MOCAA. ICI: While the museum will present an extensive collection of works from throughout the continent and abroad, how do you see international engagement through traveling exhibitions fitting into Zeitz MOCAAs future? Sven Christian (SC): International engagement through traveling exhibitions will play an important role in the realization of Zeitz MOCAAs mission to develop intercultural understanding. Another complimentary function of traveling exhibitions will be to help locate the collection within a global context, and to challenge the misconception that art from Africa is a homogenous, isolated entity. On a local level, traveling exhibitions are a great way for us to engage with parallel histories. They provide exposure to new material and offer alternate tools and approaches to problems similar to our own. Publishing Against the Grain was our first collaboration with Independent Curators International (ICI). It was also the first traveling exhibition to be held at Zeitz MOCAA. The importance of hosting traveling exhibitions like this was made evident through many of the interactions that we had with visitors over the course of the exhibition, and through the supplementary panel discussions that were held. Our attendance increased with each iteration and the large number of people who returned indicate that there is a demand for the types of discussions that the exhibition prompted. ICI: Publishing Against the Grain made its debut at the museum this fall. What about this exhibition did you and museum visitors find particularly interesting, and how can such publishing projects which disseminate alternative, progressive, and autonomous positions appeal to a Cape Town audience right now? SC: It was the scope of the exhibition and the prospect of new material that was most appealing. There were over twenty projects included in this exhibition, drawn from regions as far reaching as Peru, Uganda, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Hong Kong, and the United States. All of the core initiatives are still active today while some of their nominations were produced during the 70s, and now exist as records. Because each of these initiatives are specific to a particular time and place, we tend to think about them as isolated entities. However, having them all together in one space revealed many of their similarities. It also provided a great opportunity for us to understand the various contexts that gave birth to them, and to reinterpret these concerns and methodologies. Over the past few years, the need for alternate spaces within South Africa has become increasingly apparent. This is not to say that such initiatives are by any means newSouth Africa has a rich history of independent publishingbut that whenever a given framework is no longer able to support the needs of the voices it lays claim to, it is the unknown potential of new material that has the capacity to offer unseen solutions. In addition, the exhibition highlighted the amount of international visitors to the museum especially during the December-January period, when there is an influx of tourists in Cape Town. Many of these visitors were delighted to find publications on exhibition from their own country that they did not know existed. Being able to discover something in South Africa that was produced in your own backyard is something that I think will be important for the museum going forward, as traveling exhibitions like Publishing Against the Grain help make visible the various undercurrents that both bind and separate us. ICI: We conceived of this exhibition, as part of the curatorial framework, to generate new content and propositions at every venue. We wanted discourse to adapt to a site and the project’s changing contexts. Similarly, this exhibition continues to grow and accumulate as it travels, when new publications are added at every museum. We wanted to continue to open up a platform for discourse by inviting the curators we work with to add materials they have found influential to their particular scene. Can you explain how you framed and expanded Publishing Against the Grain for a Cape Town context? SC: The two publications I invited to take part in the traveling exhibition were Adjective and Pumflet. Adjective is an arts publication that bridges the divide between critical essay writing, poetry, and the visual arts in South Africa. Pumflet, on the other hand, is a site-specific, collaborative periodical that began as a conversation between architect Ilze Wolff and artist Kemang wa-Lehulere. As a collective they explore the relationship between the built environment and the social imagination. Like many of the initial projects drawn from ICIs international network, these publications were produced through collaborative, DIY means. They function as platforms for further research and the cross-pollination of ideas. This was something that we wanted to develop further, and became the framework for a series of supplementary panel discussions titled Alternate Voices. Alternate Voices provided visitors with a first-hand account into the origins, thought processes, and concerns behind some of the publications on exhibition. It also presented a platform for these ideas to be expanded upon within the context of artistic and critical production in South Africa. For each iteration we invited one of the core publications on exhibition to speak with one or two local practitioners. Due to their relevanceand because their concerns were common to many of the publications on exhibitionthe four that we approached were Our Literal Speed (United States), Pages (Iran and the Netherlands), Makzhin (Lebanon and the United States), and Exhausted Geographies (Pakistan). The thematic focus of each panel was drawn directly from the ideas expressed in each of these publications. For the first iteration local artists Mitchell Messina (Adjective) and Emily Robertson spoke with Our Literal Speed founders Matthew Jesse Jackson and John Spelman about their own practices and the relationship between art, capital, and popular culture. For the second, Tazneem Wentzel (Burning Museum) and Ashley Walters spoke with Babak Affrassiabi (Pages) about whether or not art could rely on the archive as a historical premise. Inspired by Makhzins open call for their upcoming issue Dictationship, the third iteration with Palesa Motsumi (Sematsatsa Library), Nick Mulgrew (Prufrock and uHlanga), and Mirene Arsanios (Makhzin) focused on the material conditions that dictate the way we write ourselves into the world. The fourth iteration was a conversation between Shahana Rajani and Zahra Malkani (Exhausted Geographies), who spoke with Ilze Wolff (Pumflet) about the long-lasting effect of the colonial blueprint in the development of former British colonies, Karachi and Cape Town. I hope our discussions will be useful to future audiences as it offers fresh insight into the motivations that underpin some of the projects in the exhibition. I think our conversations also provided an interesting perspective into how these projects were interpreted by Cape Town audiences, and will give some background into the two publications invited by Zeitz MOCAA Adjective and Pumflet which I’m very excited to see grow wings and continue on the tour.